As companies have begun making deep cuts, several examples have emerged of how to make and communicate tough decisions in a crisis – laudable ones and regrettable ones alike. Kearney’s John Kurtz discusses corporate leadership, behaviors and ethics in troubled times.

A remarkable global video call, broadcast on March 19, was witnessed by thousands of Marriott employees all over the world. In the Ritz-Carlton Hong Kong, one of the company’s flagship hotel properties, the reaction was immediate: “They were all crying after the video. Not for their own jobs or even for the company as a whole, but for the special way that Arne made them feel.”

Arne Sorenson, CEO of Marriott, had delivered the bad news that occupancy and revenues were down over 75 percent, that widespread furloughs were coming and that other painful actions would likely be necessary. Yet his message made Marriott employees proud, resolute and honored to have him as their leader.

Sorenson, in determining how to proceed, had from a very early point determined that he should reduce his own salary as well as those of his direct reports. On the video, he was more specific, announcing that he and Chairman Bill Marriott would not take a salary for the remainder of 2020 and that the other executives’ salaries would be reduced by half.

Let’s be clear: It is rare that the act of cutting executive compensation has anything but a tiny impact on the company’s financials. Virtually no company is making decisions like these due to the impact on cash preservation or the standalone benefit to the P&L. In a smaller, family-owned company, it can make a real difference to stop paying salaries to all owners. But in large corporations, it’s not about the money; it is about the values the action communicates.

Timing Matters

Already deeply respected by Marriott associates around the world and by the “ladies and gentlemen” of the Ritz-Carlton Hong Kong, Sorenson had openly discussed since late 2019 his battle with cancer. He in fact appeared bald on the video, the result of chemotherapy. Sorenson’s personal sacrifice and struggle was thus known to all the Marriott employees who knew their own jobs were at risk.

Crises have a way of very quickly separating great leaders from the rest: Andrew Cuomo’s approval rating on March 30 reached 87 percent for how he was handling the crisis in New York State — including 70 percent of Republicans. He had never been within range of these numbers in all his years of public service.

Leaders like Cuomo and Sorenson display common traits: clarity and frequency of communication, the willingness to speak the truth about previously unimaginably bad news and indefatigable energy all play a part. Above all, they both have found a way to convey that they are out in front and willing to face the challenge head on.

“I will not ask anyone to do something that I would not do” Cuomo said. Sorenson’s Marriott associates sensed the same message from him.

Alongside Sorensen, there have been other CEOs who stepped up early to announce news of their own compensation reductions to zero – notably GE’s CEO, H. Lawrence Culp, and Disney’s Chairman, Robert Iger. Many other CEOs have announced somewhat less dramatic reductions for themselves and their teams — 20 percent seems to have been a popular number (Vogue, JetBlue, TriHealth and Hallmark, among many others).

Sometimes these announcements have come at the same time as furloughs and RIFs (reductions in force) have been announced; in other cases, the executive announcements have come first, to be followed days later by other moves.

Through a systematic review of news reports and corporate press releases as well as through my own conversations with global CEOs, it is clear that it is critical to think through some key questions:

- What’s in a number? How much does it matter what level of cuts and reductions are announced for executives? Is there a special responsibility that chairs and CEOs must take?

- Does the timing and sequencing matter? Is it best to announce all moves at once or to take a different approach?

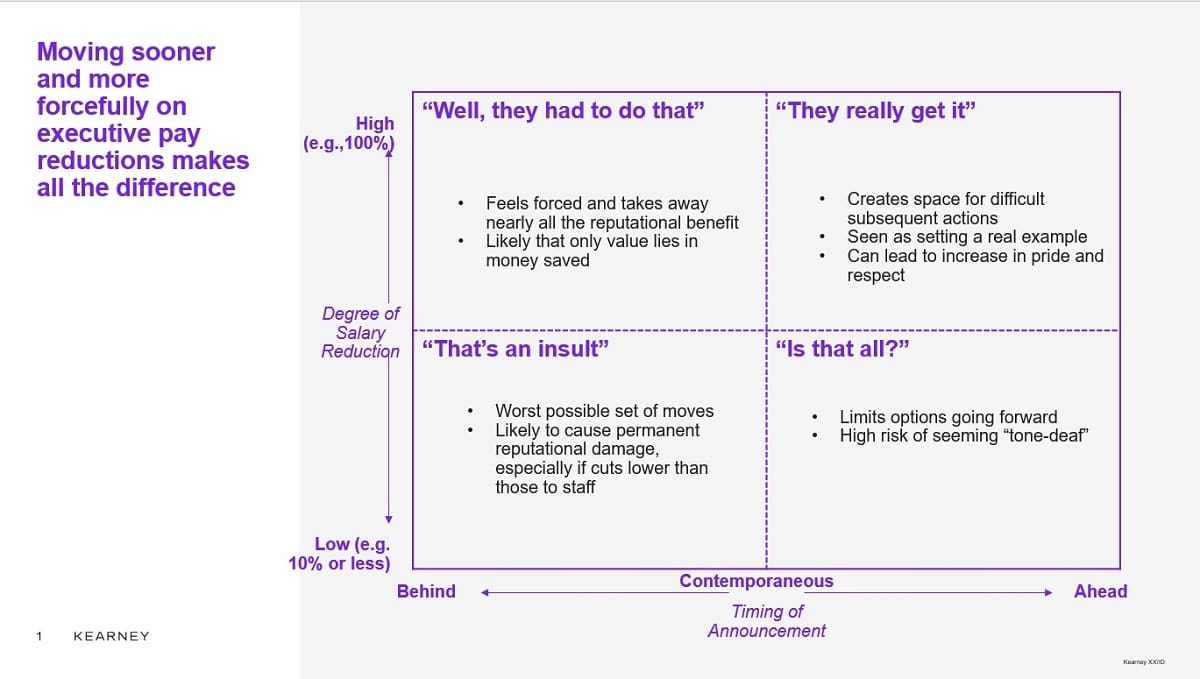

The range of options and the right answer is informed perforce by each company’s specific context. But it can be useful to be guided by the chart below, which suggests some of the reactions to decisions company leaders have made with regard to reductions in compensation for themselves and their teams:

CEOs and board chairs who announce reductions to their own pay first and make substantial reductions end up with substantial advantages over leaders who either move later or do not do enough.

CEOs and board chairs who announce reductions to their own pay first and make substantial reductions end up with substantial advantages over leaders who either move later or do not do enough.

In a scenario where a leader announces soon after a crisis begins that she or he is taking no salary until the crisis is resolved or better understood, she buys herself room to make the difficult decisions. That is, all employees are aware that there’s something coming and likely can accept a wider and deeper range of reductions when they are announced. A CEO who has announced he is taking no salary has far more room to announce furloughs, widespread pay reductions or even layoffs than a CEO who has reduced salary by, say, 10 percent. By announcing early, the news sinks in and the action stands out as an act of sacrifice.

On the other hand, if the CEO or management team’s reduction is announced contemporaneously with employee actions, a less positive result is common. This course of action runs the risk of inviting unfavorable comparisons with the other actions. In a scenario where, for example, the leadership team’s compensation is cut 15 percent and there are widespread furloughs or salary reductions for employees, there is an almost inevitable comparison of the magnitude of the actions.

Alongside the fact that most companies have had for years huge pay discrepancies between executives and rank-and-file employees, people understand that future and past bonuses, stock, options and other compensation schemes mean that a 15 percent cut is not much of a hardship, especially for a long-serving senior executive. While the same could be said to be true even of a 100 percent reduction, this move has the advantage of being absolute: There’s no higher amount than refusing all of one’s salary.

Announcing board- or executive-level reductions only after other compensation moves have been announced can be a very problematic route. Even if the reductions are significant in percentage or absolute terms, the risk is high that the decisions are seen to have been taken as an afterthought or as the result of pressure or guilt-after-the-fact — a kind of recovery from having failed to make announcements in the first place.

As we look across industries, one can see executives struggling with how to make the right decisions; the territory feels fraught with landmines. In the airline industry, the actions have ranged from United CEO and Chairman Oscar Munoz’s 100 percent cut in his salary through June to a 10 percent pay reduction for the remainder of 2020 for Gary Kelly of Southwest.

These moves – especially in an industry where share buy-backs and large bonuses and option awards can boost total compensation into eight figures – can invite scrutiny and questions: “Why only through June when employees will suffer for far longer?” or “What’s 10 percent to a highly compensated executive?” Fraught indeed.

Consider Perception

This leads to a third important question: “Is there a meaningful distinction between the perception created by salary reductions versus bonus cuts or deferrals?”

On this topic, there are several points to be made. First, foregoing bonuses at the upper reaches of a company is often, in terms of the dollars at stake, a far greater sacrifice. Yet in a year where for many companies, three months of COVID-19 has already wiped out all semblance of financial health, an announcement of bonus reductions this year may seem like a vegetarian promising to eat no meat.

The second point to remember is that salaries, to nearly all employees, are felt to be a right, whereas bonuses are seen as a privilege. Salary reductions, therefore, are both more painful and difficult to carry out, notwithstanding legal restrictions. The corollary to this is that the CEO who reduces her salary is seen to be really sacrificing, especially when it is for a long period and a significant percentage. Announcing no bonus, even if the dollar value of the reduction is very high, will not likely be seen as positively by the workforce as would a significant salary cut to the CEO.

Situations differ widely, yet it is crucial that CEOs and other high-ranking executives exhibit great sensitivity in times of strain for their companies. Arrogance that is forgiven or overlooked – in light of impressive results, skillful innovation or commanding presence – is amplified and long remembered at a time of crisis.

This is especially true when a company’s stated mission and published purpose or vision refers to the importance of its employees or the relationships with its partners (suppliers), or when a company talks proudly of its impact on the world or in its own community. Elon Musk’s brother, Kimbal, was recently lambasted in a Huffington Post story for breaking promises to the employees of his Next Door restaurant chain after repeatedly referring to them as “family.”

A company that proudly declares its caring relationships with all its stakeholders would do well to have its board watch very closely as it goes through the difficult decisions required of leadership during a crisis. Where’s the balance between looking after the company’s shareholders, employees, partners and community?

While there are no easy decisions, a framework that carefully outlines a logical order to the actions a company will take is immensely important. For global companies, this is even more complex: Each country’s culture and legal and regulatory frameworks intersect and inform decisions. Companies have to be careful to not cut more deeply just because some countries make that easier. Similarly, they must take great care to understand the messages that matter from one culture to another.

HP’s relatively new CEO Enrique Lores has earned the deep respect of his global team through his messages during the COVID-19 period. “He has inverted the messages about the customer coming first and made us know that it is our own health, the health of our families and then the customer that he cares about most,” said one longstanding employee. “It is impressive.”

At HP, whose values and “The HP Way” were established by its founders, David Packard and Bill Hewlett, Lores has tapped deeply into what matters most to HP employees. Lores’ personal style and humility has been touching to many: “It solidifies our belief in the company.”

CEOs would do well to be led by the example set by Arne Sorenson, his Hyatt counterpart Mark Hoplamazian, by Enrique Lores and others; there’s no substitute for self-sacrifice and strong, rooted values — especially in a time of great sadness and strain on the lives of your people.

Acts of true leadership, when we all emerge eventually from the fog and cruelty of COVID-19, will be long remembered. No complex theory or treatise is necessary. Values matter. CEOs and board chairs can find clarity from one of the simplest of all aphorisms: lead by example.

John Kurtz is an expert on leadership and board governance and a partner in the Leadership Change & Organization practice of

John Kurtz is an expert on leadership and board governance and a partner in the Leadership Change & Organization practice of