When AI generates an unexpected or incorrect result, it often cannot explain the reasoning behind it — because there is none. AI does not follow a line of thought or moral framework; it calculates probabilities. That’s why human review remains essential: Only people can judge whether an outcome makes sense, aligns with context or upholds fairness and ethical standards. Strategic finance and compliance leader Tahir Jamal argues that true governance begins not when systems detect anomalies but when humans decide what those anomalies mean — and understanding that difference is critical to ensuring accountability.

AI has transformed how organizations detect risk and enforce compliance. Dashboards flag anomalies in seconds, algorithms trace deviations with precision, and automation promises error-free oversight. Yet beneath this surface efficiency lies a deeper paradox: The more we automate control, the easier it becomes to lose sight of what governance truly means.

Governance has never been about control alone. It has always been about conscience. AI can audit the numbers, but it cannot govern the intent.

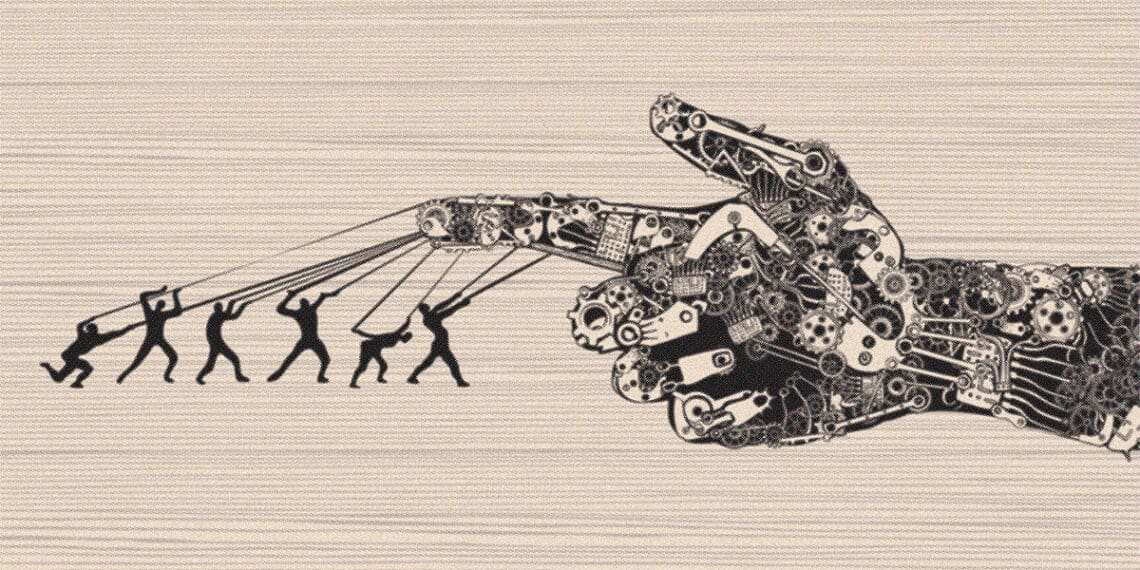

Automation often creates an illusion of control. Real-time dashboards and compliance indicators may project confidence, but they can also obscure moral responsibility. When decisions appear to come from systems rather than people, accountability becomes diffused. The language shifts from “I approved it” to “the system processed it.” In traditional governance, decisions were connected to names; in algorithmic systems, they’re connected to logs.

As organizations rely more on machine intelligence, the danger grows that leaders will mistake data for judgment. When compliance becomes mechanical instead of moral, governance loses its meaning. This illusion of algorithmic authority forms the starting point for rethinking how humans must remain at the center of governance — not as bystanders but as interpreters of ethical intent.

When data meets conscience

During my tenure leading financial reforms under a US government–funded education project in Somalia, we implemented a mobile salary verification system to eliminate “ghost” teachers and ensure transparent payments. The automation worked: Every teacher’s payment could be verified. Yet a recurring dilemma revealed AI’s limits. Teachers in remote regions often shared SIM cards to help colleagues withdraw salaries in no-network zones — a technical violation but a humanitarian necessity.

The data flagged it as fraud; only human judgment recognized it as survival. This experience exposed the gap between compliance and conscience — between what is technically correct and what is ethically right.

The same dilemma exists in corporate contexts. Amazon’s now-retired AI hiring tool automatically favored résumés from men because it learned patterns from biased historical data. The Apple Card controversy in 2019 revealed that women received lower credit limits than men despite similar financial profiles. In both cases, algorithms were consistent — but consistently biased. These examples remind us that automation can amplify bias as easily as it can prevent it.

In corporate finance, healthcare or supply chains, AI can quickly spot what looks unusual — a strange payment, a questionable claim or a sudden price change. But recognizing a pattern isn’t the same as understanding it. Only people can tell whether it signals fraud, urgency or a genuine need. As I often remind my teams, “Machines can highlight what’s different; humans decide what’s right.”

The Futurist’s Paradox: Advanced Technology, Age-Old Compliance Challenges

Radical futures will demand the same thing today's high-stakes projects require: accountability, clarity and trust

Read moreDetailsBeyond explainability: Building human-centered governance

“Explainable AI,” the idea that automated decisions should be reviewable by humans, has become a popular phrase in governance circles. Yet explainability is not the same as understanding, and transparency alone does not guarantee ethics.

Most AI systems, especially generative models that create outputs like reports or forecasts based on learned patterns, operate as black boxes with internal logic that is often opaque even to their designers. They don’t reason or weigh options as humans do; they simply predict what seems most likely based on previous data.

When an algorithm assigns a risk score or flags a transaction, it performs pattern recognition — identifying trends, such as unusual payments or behaviors — but it does not understand intent or consequence. So when a system produces an unfair or biased result, it may show which factors influenced the decision, but it cannot explain why that outcome is right or wrong.

Explainability is what builds trust in AI-driven systems, not automation. True governance therefore demands interpretation, not just inspection. For compliance leaders, AI outputs should always be treated as advisory rather than authoritative. Audit trails need human interpretability and accountability.

To make governance human by design, organizations must integrate ethics into their system architecture:

- Define decision rights: Every algorithmic recommendation should have a responsible human reviewer. Traceability restores ownership.

- Require interpretability, not blind explainability: Leaders must understand enough of the system’s logic to question it. A decision that cannot be challenged should not be implemented.

- Establish ethical oversight committees: Boards should review model behavior — fairness, inclusion and unintended impact — not just performance.

- Maintain escalation pathways: Automated alerts must trigger human judgment. Escalation keeps ethical intervention alive.

When technology serves human conscience — rather than replacing it — governance becomes both intelligent and ethical. The real measure of AI maturity is not predictive accuracy but moral accountability.

Restoring integrity in the age of automation

As AI becomes embedded in every audit, workflow and control, the challenge is no longer whether machines can govern efficiently but whether humans can still govern wisely. Governance is not about managing data; it is about guiding behavior. Algorithms can optimize certain compliance functions, but they cannot embody ethics.

To lead in this new era, organizations must cultivate leaders fluent in both code and conscience — professionals who understand how technology works and why ethics matter. Future compliance officers will need as much literacy in algorithmic logic as they have in financial controls. They will serve as translators between machine precision and human principle, ensuring that innovation never outruns accountability.

Tahir Jamal, MBA, CFC, is a strategic finance and compliance leader with more than 20 years of global experience across South Asia, the Middle East, East Africa and the US. He has directed multimillion-dollar projects in both nonprofit and for-profit sectors, leading internal control, risk management and accountability initiatives in complex environments including Somalia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. He specializes in building resilient compliance systems that integrate culture, ethics and operational realities, helping organizations strengthen integrity, ensure compliance and achieve sustainable growth.

Tahir Jamal, MBA, CFC, is a strategic finance and compliance leader with more than 20 years of global experience across South Asia, the Middle East, East Africa and the US. He has directed multimillion-dollar projects in both nonprofit and for-profit sectors, leading internal control, risk management and accountability initiatives in complex environments including Somalia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. He specializes in building resilient compliance systems that integrate culture, ethics and operational realities, helping organizations strengthen integrity, ensure compliance and achieve sustainable growth.