The 2005 docudrama Syriana captured the moment just before FCPA enforcement reached the great heights we’ve come to expect today. Anne Eberhardt theorizes on the areas where authorities may focus next.

The makers of the film Syriana posed several intriguing questions. Just how poisoned by Big Oil is the American foreign policy establishment? What exactly is Syrian about a film that hops between Iran, D.C., Lebanon, Switzerland, Spain and an unnamed Persian Gulf kingdom? How much weight did George Clooney gain, and seriously, how on earth did he lose it again?

The biggest mystery of all, though, was the screenwriter’s decision to include as a significant subplot a violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in a movie deploying the George Clooney-Matt Damon axis of star power.

In the more prosaic parts of the film (i.e., those that exclude Clooney and Damon), the story involves a proposed merger between a major oil company and a small one that has negotiated the drilling rights to important oil fields in Kazakhstan. Officials from the Justice Department just know that the only way in the living aitch-ee-double-toothpicks those rights could have been obtained was through nefarious methods: in a word, corruption. An ambitious partner at a genteel D.C. law firm is given the assignment to identify the least number of human sacrifices the Justice Department will require to allow the merger to proceed.

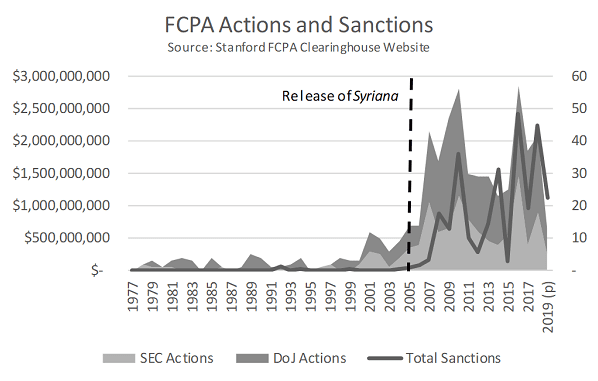

Hat tip, then, to screenwriter Stephen Gaghan for anticipating the government’s war on foreign corruption that we have all come to know and love. Syriana, released in 2005, captured that moment on the brink of – but not yet in the thick of – the present climate of FCPA enforcement. The chart below aggregates the history of FCPA actions and sanctions by the combined forces of the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission, illustrating that the period preceding the film’s release marked the very beginning of a significant uptick in enforcement.

So why the FCPA? There are so many other acts of Congress that don’t receive nearly the level of hawkeyed scrutiny from enforcement officials. Was this enforcement push a concerted effort by a presidential administration focused like a laser beam on rooting out global corruption? Or are there other explanations? And what other laws might the government decide to enforce in the future with similar enthusiasm?

So why the FCPA? There are so many other acts of Congress that don’t receive nearly the level of hawkeyed scrutiny from enforcement officials. Was this enforcement push a concerted effort by a presidential administration focused like a laser beam on rooting out global corruption? Or are there other explanations? And what other laws might the government decide to enforce in the future with similar enthusiasm?

A Little Perspective

Over the life of the FCPA, the U.S. government has collected about $14 billion in sanctions from the hundreds of FCPA actions pursued by both the DOJ and the SEC. More than 90 percent of those sanctions have been assessed since the inauguration of President Obama in 2009.

And while critics of the current president argue he is soft on corruption – if not the embodiment of corruption itself – more sanctions were assessed in 2018 than in the 30-plus years’ worth of presidencies prior to President Obama’s. As in Presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, both George Bushes and Bill Clinton.

Aggressive enforcement of the FCPA, then, does not seem to be driven by ideology. While it is arguable that the regulators’ pursuit of FCPA crimes under President Obama could have been interpreted as some sort of vengeance for the unpunished crimes of the Great Recession, that interpretation overstates forces that were already in motion and that were independent of the person occupying the Oval Office. Those forces include the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank Acts’ reporting requirements for SEC registrants, the dramatic advances in data storage and analytical capabilities, the greater culture of accountability within government and, of course, the increasingly globalized economy.

While some observers argue that the fines and penalties collected by the government have been a way to reduce the federal debt, the truth is that $14 billion in sanctions collected over a period of more than 40 years is a relatively trivial amount of money to the federal government. By way of comparison, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have received over $190 billion since the 2008 financial crisis, have paid total dividends exceeding $300 billion and now routinely return at least $14 billion each year in the form of senior preferred dividends. In any event, with the national debt currently totaling about $22 trillion, the government would need to collect $14 billion every year for more than 1,500 years to pay it off.

Perhaps the answer to the question of why FCPA enforcement has been so aggressively pursued lies in the fact that it is not the kind of hot-button issue that sparks flashes of Twitter outrage. Almost no one feels bad when they wake up to a headline announcing a large multinational corporation has been ordered to pay a hefty fine for bribing foreign officials on the other side of the planet. That is, if they even notice the headline at all.

Furthermore, while each of us may disagree about who the corrupt are, virtually all of us believe that corruption is bad. Even leaders who are themselves corrupt can be counted upon to speak out against corruption. Prosecuting foreign corrupt activity, then, is relatively painless for politicians.

What to Look For

Are there any signs pointing to where Johnny Law will next ride up on his noble steed, the sun reflecting off the silver star pinned to his chest, his pristine 10-gallon hat providing the shade he requires to gaze clear-eyed into the promising future of justice for all?

Already we have begun to see large fines and criminal prosecution for crimes against the environment with the emissions cheating scandals. We are also beginning to see penalties assessed for egregious activity involving the marketing of highly addictive prescription drugs. And who among us has not breathed a sigh of relief at the announcement of penalties against companies that were not sufficiently diligent in safeguarding our consumer data?

Looking ahead, how long will it be until we see companies prosecuted for violations of human-trafficking laws? Or for their participation in the extraction of minerals from conflict zones? Or for violating consumer (or patient or employee) rights?

If the past is a guide, regulators will continue to target large, multinational corporations that are perceived to violate laudable – and relatively uncontroversial – public policy goals.

Anne Eberhardt, CFE, CAMS, is a Senior Director in the Valuation and Litigation Consulting practice at

Anne Eberhardt, CFE, CAMS, is a Senior Director in the Valuation and Litigation Consulting practice at