Since it went into effect nearly a year ago, the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act illustrates how the “E” and “S” in ESG have a tendency to overlap. ESG columnist John Peiserich shares his take on this intersection and why it means compliance teams may need to create new math.

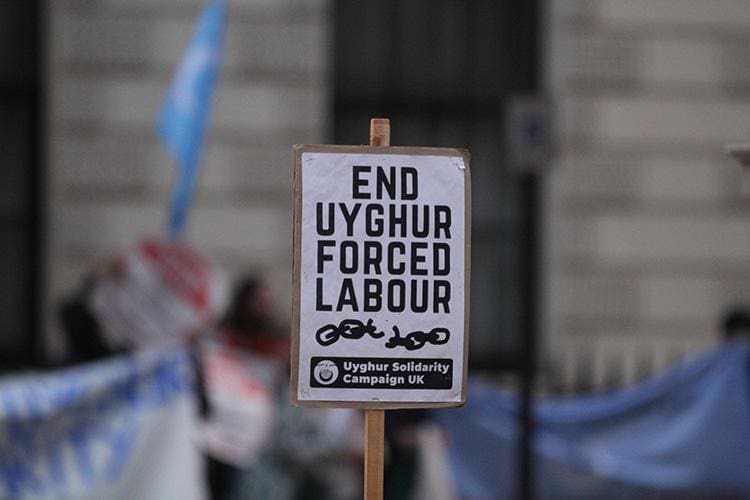

Sustainability and ESG sometimes have strange bedfellows. The social and governance components of both face ever increasing complexity. Effective June 21, 2022, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) creates a rebuttable presumption that goods mined, produced or manufactured wholly or in part in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China were made with forced labor, including labor by persecuted minorities in other areas of China and are therefore ineligible to enter the United States.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is authorized to detain, seize or exclude such goods and issue civil penalties against those who facilitate such imports.

Products included

The act applies to downstream products that incorporate region-produced goods as components and/or to companies on the entity list regardless of where the products were manufactured or from where they were shipped. It also applies to all companies regardless of size or sector. Likewise, there is no de minimis amount of materials imported that are considered acceptable.

High-priority sectors for enforcement include agriculture (the region accounts for 25% of the world’s tomatoes), fashion (the region accounts for approximately 20% of the world’s cotton production) and silica-based products (45% of the world’s polysilicon is produced in the region). The silica enforcement priority is based on silica being “a raw material that is used to make aluminum alloys, silicones and polysilicon, which is then used in buildings, automobiles, petroleum, concrete, glass, ceramics, sealants, electronics, solar panels and other goods.”

Timelines & compliance information

Enforcement timelines are tight, and while we are more interested in the interface with sustainability, these tight timelines necessitate early efforts well before the time begins to run against the importer. CBP has five business days to decide whether the goods should be detained at the port of entry. If there is no determination within five days, the goods are considered detained. At that point, the importer has just 30 days to challenge the detainment, including obtaining any necessary documentation to support importation.

The information needed to comply with the act is similar to the information that companies utilize for sustainability tracking. To avoid detained goods, companies will need to provide:

- Due diligence information

- Supply chain information

- Supply chain management details

- Specific to the act, evidence that goods originating in China were not the result of forced labor.

Direct supplier evaluations, in the form of independent third-party audits, are just part of the due diligence process under the act and are likely much more complicated audits than supply chain review for sustainability purposes, i.e., Scope 3 reporting.

What Companies Around the Globe Need to Know About EU Sustainability Reporting

By the beginning of next year, large companies in the EU or that do a substantive amount of business in EU countries will be required to issue sustainability disclosures under new rules. ESG columnist John Peiserich sorts through the details.

Read moreDetailsMitigating risks associated with the act

The requirements under the act, in addition to creating supply chain disruptions, also create risk associated with governmental reporting. Companies routinely commit to avoiding child or forced labor as part of sustainability and voluntarily report on their progress separately from regulatory- or compliance-driven filings. These efforts are typically managed separately, and many are not managed by the same corporate teams.

It is becoming more and more essential to identify the key areas of interest across the corporate structure. Stakeholders should be identified, listening sessions conducted, and agreement reached (including at the senior management level) as to what issues are key to the success of the company, including profitability. Once those key areas have been identified, corporate policy and procedures can be established which help avoid the risk of conflicting sustainability efforts and regulatory requirements.

Conclusion

The act is just one recent example of the overlap between sustainability and pure compliance. The risk associated with noncompliance with the act is great from a pure compliance standpoint and could disrupt an entire supply chain. Additionally, that same noncompliance has an adverse impact on corporate sustainability efforts and is likely to result in reputational impacts both internally and externally.

This law also sets the stage for “S” efforts that look more like formal metrics more typically found in “E.” Many “S” efforts are soft science-driven without qualitative and quantitative metrics. Being able to demonstrate act compliance will necessitate creating policies and procedures that have metrics, i.e., zero use of child and forced labor, that can be followed and documented. These compliance activities will result in stronger “S” practices, which enhance sustainability as well.

John Peiserich is a senior vice president in J.S. Held’s Environmental, Health & Safety — Risk & Compliance group. With over 30 years of experience, John provides consulting and expert services for heavy industry and law firms throughout the country with a focus on oil and gas, energy and public utilities. He has extensive experience evaluating risk associated with potential and ongoing compliance obligations, developing strategies around those obligations, and working to implement a client-focused compliance strategy. He has appointments as an independent monitor through EPA’s Suspension and Debarment Program. John routinely supports clients in a forward-facing role for rulemaking and legislative issues involving energy, environmental, oil and gas, and related issues.

John Peiserich is a senior vice president in J.S. Held’s Environmental, Health & Safety — Risk & Compliance group. With over 30 years of experience, John provides consulting and expert services for heavy industry and law firms throughout the country with a focus on oil and gas, energy and public utilities. He has extensive experience evaluating risk associated with potential and ongoing compliance obligations, developing strategies around those obligations, and working to implement a client-focused compliance strategy. He has appointments as an independent monitor through EPA’s Suspension and Debarment Program. John routinely supports clients in a forward-facing role for rulemaking and legislative issues involving energy, environmental, oil and gas, and related issues.