Compliance Officers Assume Personal Liability

The ex-compliance chief of MoneyGram International Inc. (MoneyGram) is found personally liable for MoneyGram’s AML failures. The lawsuit is unprecedented in growing regulatory efforts to impose personal liability on a compliance officer for a company program failure. Patty Tehrani offers an analysis of the settlement and lessons for compliance practitioners.

Since 2014, compliance officers have been monitoring the government’s case against Thomas Haider, the ex-compliance chief of MoneyGram International Inc. (MoneyGram). Haider was sued for failing to ensure MoneyGram had an effective anti-money-laundering program. The lawsuit is part of growing regulatory efforts to impose personal liability on a compliance officer for a company program failure.

Before we address the liability issue, let me summarize the case:

- Haider was MoneyGram’s Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) from 2003 to 2008.

- Haider had direct oversight over MoneyGram’s Fraud Department and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Compliance Department.

- Haider also had the authority to implement a policy for terminating or otherwise disciplining MoneyGram agents and outlets. The Fraud Department proposed that MoneyGram implement such a policy for terminating or otherwise disciplining agents and outlets that presented a high risk of fraud based on their reporting and monitoring of activities. They drafted a policy that was sent to Haider, but he never issued it.

- Haider did not structure MoneyGram’s AML Program to:

- refer information from the Fraud Department on high-risk activity to the folks responsible for filing suspicious activity reports (SARs) or

- conduct adequate audits of certain agents/outlets.

In response, MoneyGram entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) with the Department of Justice in 2012 and agreed to forfeit $100 million. FinCEN brought its complaint against Haider two years later, in 2014. Haider tried to fight the allegations but failed. Four months ago, Haider’s motion to dismiss FinCEN’s complaint was denied. His claim that the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) did not allow penalties against individual employees of a financial institution for the institution’s willful violations of the BSA’s requirement was rejected. Haider was said to be tired of fighting the matter and agreed to settle the lawsuit earlier this month with New York federal prosecutors and FinCEN. In the settlement, Haider was found liable under the BSA for failure to:

- ensure that MoneyGram implemented and maintained an effective AML Program and

- file timely SARs with FinCEN.

Haider also reluctantly (see below) admitted, acknowledged and accepted responsibility for these findings and agreed to:

- a three-year injunction barring him from performing a compliance function for any money transmitter;

- pay $250,000 (less than the $1 million FinCEN sought in its complaint, but still the largest sought by FinCEN against an individual); and

- accept responsibility for:

- failing to terminate MoneyGram outlets that were involved in fraud schemes;

- failing to establish a policy for terminating outlets that presented a high risk of fraud; and

- structuring MoneyGram’s AML program to use information properly from the Fraud Department to file SARs.

In settling this matter, Acting U.S. Attorney Joon H. Kim said that compliance officers serve “as the first line of defense in the fight against fraud and money laundering.” Acting FinCEN Director Jamal El-Hindi weighed in as well on the role of compliance professionals. “Compliance professionals occupy unique positions of trust in our financial system. When that trust is broken, it is important that we take action so that the reputations of thousands of talented compliance officers are not diminished by any one individual’s outlying egregious actions.” Both wanted to send a message to compliance professionals “that behavior like this should not be tolerated within the ranks of compliance professionals.”

While Haider had shortcomings as a CCO, should he have personal liability for MoneyGram’s AML failures? He certainly did not think so. In a statement acquired by Reuters, Haider said he supported the Fraud Department’s proposals to terminate and discipline the fraudulent agents, but was overruled by management. He also said that MoneyGram’s AML program was audited by state regulators several times and reviewed by an external consulting firm. None of these reviews flagged any of the issues cited in the lawsuit and that MoneyGram’s program was deemed satisfactory.

I don’t disagree that compliance officers perform an essential function and are critical to any organization. But this decision raises some questions for me:

- While the focus here is on AML programs, will this decision serve as a precedent for existing or future lawsuits against compliance professionals in general?

- Will this decision serve as a basis for compliance officers to become personally liable for all program failures?

- What, if any, personal liability applies to management if they reject a compliance recommendation?

- And ultimately, what effect will the Haider decision have on the compliance profession? Will this deter good, competent folks from entering the profession or cause those already in the profession to leave?

This case was intended to send a message to compliance officers, but is that the right audience or the only one for program failures? Compliance officers have long struggled to impress upon management their responsibility for corporate programs and governance. Even FinCEN’s 2014 guidance said as much:

“A financial institution’s leadership is responsible for performance in all areas of the institution including compliance with the BSA.”

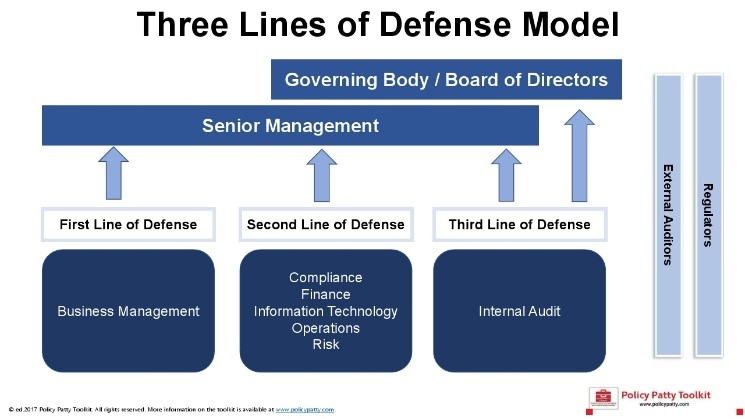

Separately, industry-accepted models underscore this point. Consider the Committee of Sponsoring Organization (COSO)’s Three Lines of Defense model. Under this model, business management serves as the first line of defense and distinguishes the three lines as summarized below:

- First line: Business unit management is responsible for identifying and managing risks directly.

- Second line: Assurance functions are the groups responsible for ongoing monitoring of the design and operation of controls in the first line of defense, as well as providing advice on and facilitating risk-management activities. They should have some degree of objectivity, but do not need to be entirely independent of the first line.

- Third line: Independent assurance functions provide assurance over the managing of controls and risks and must be independent, such as internal audit. The illustration below summarizes this model.

The key point here is that management establishes the second line functions to support their efforts under the first line of defense. This function needs to have some degree of independence from the first line of defense, but they should intervene directly in modifying and developing the internal controls needed to address identified risks. Lines are blurred from time to time, but the framework still provides that management must serve as the first line of defense. The Haider decision now provides otherwise in the context of AML, and what remains is whether this decision will be extended to other areas compliance officers cover or support.

Lessons Learned

What are some lessons learned from the Haider decision?

- Empower your compliance officers to be able to make decisions about compliance matters without interference by the business. This is a good opportunity to use this decision to impress upon your management that compliance officers without the proper authority will not serve the organization well.

- Establish an escalation process for recommendations regarding compliance-related issues that are rejected by non-compliance personnel. In such cases, compliance personnel should document their recommendations, highlighting both the rationale for certain actions be taken to ensure compliance and any possible consequences of non-compliance.

- Reassess and, where necessary, improve internal information-sharing procedures to make sure information – especially critical information around high-risk issues – gets to the right groups and personnel. And make sure to follow up to check on not only the receipt of such information, but also if any further information or action has been taken or is needed.

- Expect more collaboration and cases by regulators to seek and impose civil penalties on culpable individuals (who also potentially may face prosecution by the DOJ).

- Monitor these efforts and cases to see if regulators continue in this direction to apply liability more and more to compliance officers. It is important to remain current on these developments since you may need to factor this into your responsibilities and program controls.

Patty P. Tehrani is an experienced compliance counsel and advisor and the founder of the Policy Patty Toolkit (

Patty P. Tehrani is an experienced compliance counsel and advisor and the founder of the Policy Patty Toolkit (