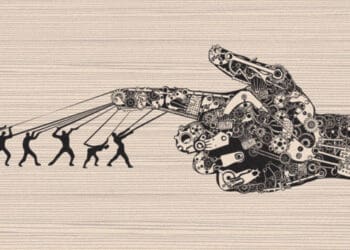

Average people with good intentions can find themselves tumbling down the slippery slope of misconduct, often starting with small steps that seem insignificant in isolation. CCI columnist Mary Shirley explores how compliance teams can partner with business units to create accountability frameworks while fostering environments where employees feel safe surfacing their own ethical missteps before they escalate.

As we diligently work on fostering and measuring our cultures of integrity, I ask: What have you done to combat your colleagues finding their way to the slippery slope of misconduct?

It can happen easily enough, perhaps more easily than you realize. Richard Bistrong is a consultant and CEO of Front-Line Anti-Bribery, and he attributes the slippery slope for the predicament he found himself in in 2009 (pleading guilty to bribery as part of an FCPA investigation). Small transgressions or not, asking more questions when someone says something that doesn’t seem quite right is often where it starts.

We give little thought to these circumstances because they seem so harmless; there’s no clear red flag waving in our faces, it’s a small pink post-it note that we readily disregard under a pile of other papers because we’ve got so much else going on, like making sales targets — and there’s only 10 days left in the quarter!

Compliance call to action

So how do we as compliance practitioners, armed with the knowledge that positioning on the slippery slope can be our last chance to salvage a situation heading in the direction of minor misconduct to major corporate scandal, address this risk?

Virtuous circles

In “The Dark Pattern” authors Guido Palazzo and Ulrich Hoffrage posit that virtuous circles can remediate against slippery slopes. They advise that “organizations should implement a zero-tolerance policy for small rule breaking, and leaders must carefully observe how and when their teams transgress seemingly harmless limits to achieve their goals. This does not mean they should punish people for small infractions … However, the clear signal top-down must be that there are ethical and legal limits to business success.”

Of course, the challenge for us is that where punishment is appropriate, we in compliance are not often the ones deciding on disciplinary action; it’s the business. The business can be extremely reticent to discipline high-value employees. If our statements of zero tolerance are not backed up with enforcement, we may be perceived as toothless.

To address this, I recommend partnering with the business around expectations related to company values to make sure that we all agree there are certain behaviors that won’t be swept under the rug. We reassure them that we won’t interfere in the particulars of decisions, but we need to be singing off the same song sheet about what zero tolerance actually means and get their commitment that they will act when appropriate, including if that means disciplining very senior staff or rainmakers.

For this and many other reasons, I am a staunch supporter of organizations having a disciplinary action framework and associated matrix that proactively sets out types of misconduct and possible disciplinary action for varying levels of misconduct. Such a document, which gives you something tangible to point to, makes it easier to hold the business accountable and create consistent punishment for misconduct, including appropriate action for small issues that may later snowball down the slippery slope.

Compliance Best Practices DOJ Should Endorse

Latest program guidance offers some details, but the more the merrier

Read moreDetailsAddressing the elephant in the room

Directly calling out the risk of the slippery slope in our compliance training and awareness initiatives can have value. Giving this phenomenon a name and exploring the circumstances in which it can happen better helps individuals in our organizations identify for themselves when they might be on a slippery slope. This increases their chances of self-accountability and removing themselves from the situation before it’s too late. They’ll also be better equipped to be accountability partners for colleagues, especially those who are confidantes to each other, better priming your organization for readiness to speak up about observed slippery slope characteristics.

This year I’ll be wrapping up my organization’s ethics and compliance week festivities with a short video discussing the slippery slope, with a real-life story of how it can go wrong, when one small step leads to another until we’re tumbling uncontrollably down the hill.

Soliciting transparency

I considered Bistrong uniquely positioned to provide some insight into mitigating the slippery slope risk environment and accompanying incremental bias, and asked from the position of a “sales guy” what he thinks compliance can do to actively reduce this risk.

“The slippery slope doesn’t have to be one, and one bad mistake, or an ethical misstep, doesn’t automatically have to lead to another one. In terms of how compliance teams can help people avoid the slippery slope mentality, the messaging should be around: If you come to us and share that you’ve made an ethical error, we will try to work with you to understand why you thought it was a good decision, even if regrettable, and how we can reverse it (if possible),” Bistrong said. “That’s not to say you’ll get a promotion for sharing your error, but if you surface your ethical misstep instead of burying it, we then have a chance to talk about it and learn from it, so there’s less likelihood that you’ll make that same mistake again.”

He continued: “The other side of that statement is that if you make an ethical mistake or compliance circumvention and we find out about it, and you didn’t tell us about it, that’s going to be treated in a wholly different manner. That’s the sort of messaging, in hindsight, that might have mitigated the risk of my ending up on that slippery slope.”

This is a good point. If someone feels comfortable telling us about a minor whoopsie before things get too bad, we’re all left with choices. It’s only when conduct is egregious that we pass the point of no return. You know what I’m talking about here, those times when we have no choice but to engage in significant disciplinary action, or further still, when it would be prudent for the employee to engage their own legal representation.

Bistrong also supplied a helpful indicator to compliance practitioners to be on the lookout for when folks are not approaching compliance to confess a compliance circumvention: “Proactive outreach is also critical to avoid dangerous silence (with credit to Amy Edmonson). If people aren’t calling you for support who should be calling you for support in high-risk areas or high-risk regions in the world, does no news mean good news? In those cases, should you be calling them to offer support and guidance? In my former career, it was dangerous silence. I wasn’t calling anyone for support in how I was getting things done in high-risk regions, and no one was asking me, especially early on in my new international role, ‘Richard, we appreciate your success, but you are new to this role and field, and we are concerned that we are not hearing from you to ask for support and assistance, so how are things out there, how can we help?’ Those are the kinds of open-ended questions that could have made a difference, especially if asked when I first started in my new role.”

So, if you’re thinking no news is good news, this might just be your sign to check in and send a little one-pager communication on the risks of the slippery slope or other compliance communications to folks in high-risk exposure positions who have been quiet recently. If you’ve not had an introductory call with a new sales staff member, now is as good a time as any.

Conclusion

Avoiding the slippery slope in a dedicated way is not often in our compliance plan, but I make the case to you that it should be. There is huge value in helping colleagues understand how dangerous slippery slopes can be, and how Average Joes who are honest, good people with good intentions can eventually find themselves at the top of the slippery slope and how to claw themselves back up the ladder of integrity.