The culture of your team is highly collaborative and positive, so much so that ethical concerns are rarely raised for fear of killing the vibe. Ask an Ethicist columnist Vera Cherepanova and guest ethicist Brennan Jacoby of Philosophy at Work talk about the pitfalls of terminal niceness and how teams with hyper-positive cultures can begin to approach the practice of ethics.

Our team has a great culture. Trust and psychological safety are strong, and everyone always says they feel highly supported. But I worry that our lovely culture might be holding us back: Our uber-positivity and supportiveness makes it hard to challenge each other. When it comes to ethics, I’m concerned that we’re not talking about each other’s morally grey behaviors for fear of being seen as too critical. How can I and my team be better at holding each other to account? — ANONYMOUS

This month, I’m joined by a guest ethicist, Brennan Jacoby, Ph.D., to reflect on a challenge that many high-functioning teams face but rarely admit. How do you hold people accountable in cultures that are overwhelmingly positive? Can accountability feel like disloyalty? And are all “good” cultures actually good for ethics?

Brennan is a philosopher and the founder of Philosophy at Work, a UK-based collective that teaches critical thinking and helps businesses cultivate cultures of ethical practice. His work sits at the intersection of performance and integrity, making him especially well-placed to weigh in. Originally from the US, Brennan is now based in the UK, where he is also a fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts.

To move forward on this issue, work to normalize an understanding of ethics and accountability across your team that is aligned with the trusting and supportive culture you want to protect. To do this, explore with your team how they think about ethics and accountability.

Unfortunately, it is common for ethics to come with connotations of shame and guilt. To say that you think the team is dealing with an ethical dilemma, therefore, might be heard by your team as a criticism. It doesn’t have to be this way, though.

If you find that your team has a view of ethics that is closely correlated with shame, then try introducing a more accurate understanding of ethics as the practice of navigating morally gray areas of life. You might find the way that Rushworth Kidder understands ethical dilemmas helpful. In his book, “How Good People Make Tough Choices,” Kidder frames ethical challenges as situations where good people feel stuck between competing “right” actions.

For example, a colleague may be caught between wanting to do what is right in the short-term vs what is right in the long-term. Or they may want to do what is right for an individual, but doing so is at odds with doing what is right for the collective.

If your team comes to understand ethics as the practice of good people making tough choices, then holding each other to account becomes positive. Rather than being about pointing the finger of blame, accountability begins with the recognition that the landscape in which you and your colleagues are operating is complex. Equally, if you or your colleague think a wrong choice was made, then the conversation about accountability becomes a search for a better way forward rather than a critique of each other’s character.

It is important that the steps you take to reframe ethics and accountability are authentic to you and your team, but a few high-level initial steps could get you started.

First, the most direct opportunity to normalize a positive understanding of ethics is at a retreat or off-site event focused on team culture. The next time your team gathers to reflect on how the team wants to “be,” you could suggest that the team extend its supportive culture to enable better strengthening of each other — in terms of performance but also ethics.

Second, if your team already has a practice for sharing personal values and preferred ways of working, you could add ethics and how you understand it to your contribution to that practice. The hope here is that the next time you all discuss what you really care about, you’d have an opportunity to introduce how you see ethics and engage others in discussing how they see it, too.

Lastly, work ethics into your project life cycles. For example, early on in a new project, when you are discussing the remit, expectations and deadlines of the project with colleagues, ask something like, “What would make this project work well for you?” After listening to their answer, if they return the favor and ask what would be positive for you, you could say something like, “I’d like us to take a really collaborative approach and not be afraid to challenge each other on things if we think the other person has missed an opportunity or gotten anything wrong.” If you both agree to such expectations, then if you ask for feedback during the project or bring up something around accountability during the project, the supportive intention behind your comment will be clearer to your colleague.

Again, it’s important that the steps you take are authentic and natural to you, but by taking these kinds of actions, you can get better at holding each other to account and help your team see that ethics and accountability are positive and supportive by their very nature.

Brennan’s point is a powerful one: Too often, ethics is treated as a “gotcha,” when it’s really a muscle for thoughtful collaboration. Ethics requires friction, and a good culture doesn’t avoid ethical tension but creates space to explore it with care. That’s something teams with strong culture should be especially well equipped to practice.

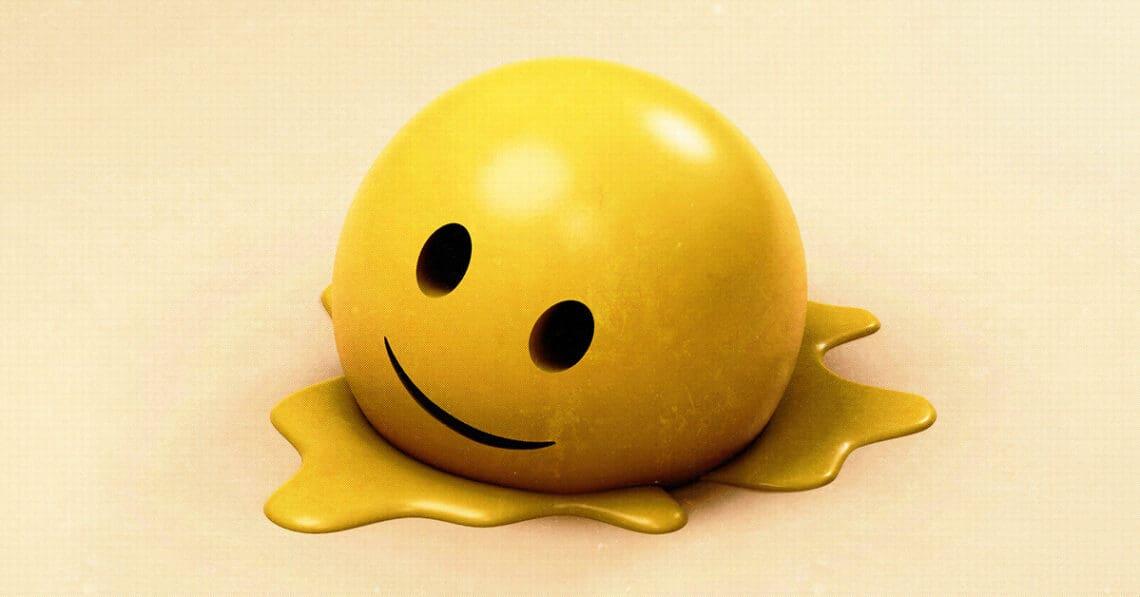

This dilemma reminds us that even “good” cultures can go too far. As “toxic culture” has become a buzzword, many workplaces have veered to the other extreme — a culture of “terminal niceness,” where conflict is avoided at all costs. But without disagreement, there’s no progress. Without feedback, there’s no learning or growth. And without moral friction, ethics becomes a slogan.

As former Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst aptly put it: “Cultures that are terminally nice are so nice that you never have the hard conversations — and you never make the hard changes until you go into bankruptcy.”

That ‘Do the Right Thing’ Mug? It’s Missing Some Fine Print.

Ethics isn’t a slogan; it’s a practice

Read moreDetailsReaders respond

The previous question came from an employee grappling with the phrase “do the right thing,” a common refrain in corporate culture. The dilemma revolved around how to interpret this guidance when ethical choices are not straightforward and how to move beyond slogans to meaningful moral reasoning in day-to-day decisions.

In my response, I noted: “Your question — What does it actually mean to do the right thing? — may sound rhetorical, but it’s one of the most serious challenges in ethics and moral philosophy. The first step in untangling this is to admit something most compliance training never does: In many situations, there may not be a single, clear-cut answer. Ethics isn’t math or accounting. It’s not about plugging values into a formula. In fact, trying to make it that tidy can backfire by encouraging false confidence or performative compliance.

“That doesn’t mean anything goes. Rather, it means that ethical reasoning involves judgment. And judgment, by definition, involves uncertainty. Competing obligations — to yourself, to others, to your organization and to something larger — and how to best satisfy them also come into the picture. A moral person doesn’t blindly follow rules; they think carefully about the consequences of their actions, how those actions align with their values and whether they’re treating others with fairness and respect. They ask how their choices reflect who they are or aspire to be.” Read the full question and answer here.

So simple and complex at the same time — JK

I think we overcomplicate things. Most of the time, we do know what the right thing is — we just don’t like the discomfort that comes with it. If something feels off, it probably is. You don’t need a moral philosophy degree to act with integrity.” — ML

Look, “do the right thing” sounds great on a poster — but in real life, it’s never that simple. On one hand, you’ve got rules and values that say “this is right, full stop” — that’s the deontological view. But when you’re running a business, especially across borders, you’re also dealing with different cultures, stakeholders and trade-offs. That’s where the “greatest good for the greatest number,” or utilitarianism, comes in. Corporate leaders are constantly caught between these two — principles vs. consequences. The job isn’t to blindly follow a rule but to wrestle with the context and own the decision. And, yeah, that means being ready to explain not just what we did, but why. — AK

Vera Cherepanova

Vera Cherepanova