Assumptions are dangerous. Sam Sheen, financial crime expert at Efficient Frontiers International (EFI) shares the story of a criminal who seemed above board but would certainly have been found out sooner with proper customer due diligence.

Have you ever seen dogs at the airport sniffing around the bags?

These sniffer dogs play a critical role in the story of a Ph.D. and Cambridge By-Fellow who took a mighty tumble from the ivory tower thanks to unchecked greed and a lack of due diligence on the part of the institutions funding his work.

Here, I outline some of the potential “blind spots” in relation to the fraudster and the bank accounts involved.

The Doctor and His Work

A university academic and Ph.D. in Engineering, the Doctor was Iranian born and later became a British citizen. He still had family who lived in Iran, and he was known to travel there to visit them.

He completed his postdoctoral studies and acted as a By-Fellow at one of the colleges of Cambridge University. The Doctor was considered highly accomplished in developing new technologies in the field of renewable energy, even winning international acclaim in 2006 for his work on wind turbine technology.

Over the years, either solely or in conjunction with other academics, he incorporated several companies. Information about the companies, their directors and shareholders were available on the Companies House register. Their accounts were not on the register, as they had qualified for an exemption.

The energy projects were funded in part by government grants, the terms of which stipulated what the funds could be used for. Many of the grants only covered the expenses incurred by the projects; they were not intended to cover personal expenses.

The Illicit Activity and the Doctor’s Ill-Gotten Gains

Two of the companies, Company A and Company B, in which the Doctor was a director and shareholder, applied for grants from both the U.K. government and the EU. These companies were described in publicly available materials as offshoots from the Cambridge University Engineering Department.

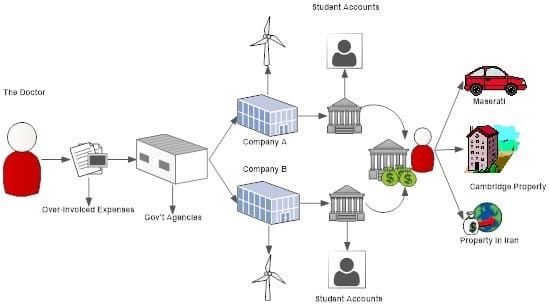

The agencies required proof of the expenses incurred before paying the grant. The Doctor created invoices and had them issued by Companies A and B to the government agencies. In those invoices, he inflated the size of expenses actually incurred by the projects.

So, while the projects themselves were legitimate, the Doctor was inflating the costs incurred so that the whole amount of the project would be covered by the grant, instead of just the actual costs incurred. This meant that Companies A and B received more money in grants than that to which they were entitled. The Doctor also falsified bank statements to support the inflated expenses he submitted.

Sadly, the Doctor’s main motivation behind this scheme was greed. He siphoned funds from Company A’s and Company B’s bank accounts for his own personal benefit, employing methods including using the bank accounts of some of his Ph.D. research students to receive what were referenced as “studentship payments” to try and avoid detection, with the money then being transferred into his own personal accounts.

Analysis of the Doctor’s personal accounts by the NCA showed that he had withdrawn more than £820,000 in cash from his personal account over a period of just under four years. That money was used to fund the Doctor’s lavish lifestyle, including the purchase of a property near Cambridge, a property in Iran and the lease of a Maserati sports car. NCA investigators also believe he took hundreds of thousands of pounds to Iran, where some or all of it was invested in property totaling approximately £900,000.

Analysis of the Doctor’s personal accounts by the NCA showed that he had withdrawn more than £820,000 in cash from his personal account over a period of just under four years. That money was used to fund the Doctor’s lavish lifestyle, including the purchase of a property near Cambridge, a property in Iran and the lease of a Maserati sports car. NCA investigators also believe he took hundreds of thousands of pounds to Iran, where some or all of it was invested in property totaling approximately £900,000.

Blind Spots

The blind spots in this case are numerous – both for the banks who operated the accounts for Companies A, B and the Doctor in terms of the CDD undertaken by them. Some seem obvious, while others may have been informed by perceptions around professions, account use and a customer’s activities. Here are a few I’ve identified (I’m sure you can also spot others):

The Doctor

Large bank balance – The Doctor was an engineer and teacher at university. Do teachers really make that much over a four-year period? Was there any evidence that he had commercialized any of the projects he had worked on?

Workplace – The Doctor was a teacher at Cambridge, a reputable institution, which must check professors… Was the assumption, then, that he must have been low-risk?

Profession – The Doctor worked in renewable energy, a socially responsible field of work, and had a track record of receiving grants as a professor. Was the assumption, then, that he must be low-risk?

Travel – The Doctor frequently traveled to Iran, his family resided there and he made large cash withdrawals, which he blamed on sanctions. Was this a reasonable explanation? (see more about this below)

Companies A and B

Nature of Business – The companies operated in renewable energy, a socially responsible field of work. Was this assumption that they must be low-risk?

Grants – The companies’ grants were awarded by government bodies, which must be checked before grants are given to make sure applicants are fit and proper. Was the assumption, then, that they must be low-risk?

Directors and Controllers – Is there a common authorized signatory across Companies A and B? If so, why not dual signatories?

Companies House Filings – There was an exemption from accounts filing vs. actual account activities. Was this consistent with expected account activity?

A Box of Chocolates: The Doctor’s Apprehension and Imprisonment

Now, back to those airport dogs sniffing the bags.

Apparently, the Doctor, despite having travelled to Iran on several occasions, appeared to have forgotten about the sniffer dogs, which are used to detect currency stashed in hand luggage.

In 2015, the Doctor attempted to board a flight to Tehran when “Buddy” the airport dog identified something unusual in his hand luggage. The Border Force officers found £137,000 in cash.

The Doctor claimed he was bringing the money for personal use in Iran because he was unable to transfer the money through the banking system due to strict sanctions. He produced the bank account statements and invoices mentioned earlier to demonstrate his “wealthy background.” On a second trip, he tried to bring £100,000 in his hand luggage inside boxes of chocolates. He tried to use the same documents to explain this second bundle of cash he was bringing to Iran.

In the end, a full investigation was initiated by the National Crime Agency (NCA) into the Doctor. Earlier this year, the Doctor was sentenced to serve four years in prison for fraudulently claiming £2.5 million in government grants. He was also disqualified from acting as a director of a company in England for at least seven years.

The Case for Customer Due Diligence

With this story in mind, it should go without saying that conducting customer due diligence (CDD) on new customers is a must. It is a key component of an effective anti-financial crime (AFC) compliance program, with a great deal of effort often invested in gathering information about a new customer, including their date of birth, place of residence and, in the case of a corporate entity, their date of incorporation and memorandum and articles of association.

It’s essential when performing CDD on new customers that the goal of this exercise is not lost among the policies and procedures. The aim is to develop a clear picture so that the business can get a good idea about the nature and purpose of that relationship (i.e., why the customer wants a product and how they plan to use it) and quickly detect when activities take place that are inconsistent with that picture.

Failing to assemble a clear and complete risk profile of a new customer can create “blind spots” – or areas where risks arise that are not detected. This can often occur when a business has made certain assumptions about a customer’s profession based on assumptions about whether they are “trustworthy” or “reliable.”

Assumptions – as in this case of the Doctor – can prove to be entirely unreliable.

Sam Sheen is a Financial Crime Advisor at

Sam Sheen is a Financial Crime Advisor at