The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976 (HSR Act) governs the timing of mergers, acquisitions and other transactions — and failure to comply can carry significant penalties. But firms and advisers should be aware of a raft of recent changes, which Nelson Mullins partner Carrie Hanger and her co-authors explore.

The HSR Act governs the time for all closings for covered mergers, acquisitions and other transactions, and failure to comply with its requirements can carry significant consequences, including daily penalties for noncompliance.

But changes to those requirements have caused upheaval in recent years. Some changes, such as the switch to electronic filing, have been lauded. Others, such as the “temporary” suspension of early termination of HSR waiting periods and the reversal of previously stated enforcement positions, have been met with concern.

All these changes, however, call on all entities and advisers engaged in merger and acquisition activity to pay special heed to the developments summarized below, which signal greater scrutiny for proposed transactions and a broader view of HSR reportability moving forward.

The HSR Act requires that parties to certain mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures and other transactions notify the Premerger Notification Office (PNO) of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ) prior to the consummation of the transaction. The purpose of HSR reporting and notification is to enable federal antitrust agencies to identify problematic transactions in their preliminary stages, rather than having to unwind them post-closing. When a HSR filing is required, the parties must observe the prescribed HSR waiting period before the transaction can close. In most cases, the HSR waiting period is 30 days; however, the waiting period is only 15 days in bankruptcies and cash tender offers.

Good news first: 2022 reporting thresholds went (way) up.

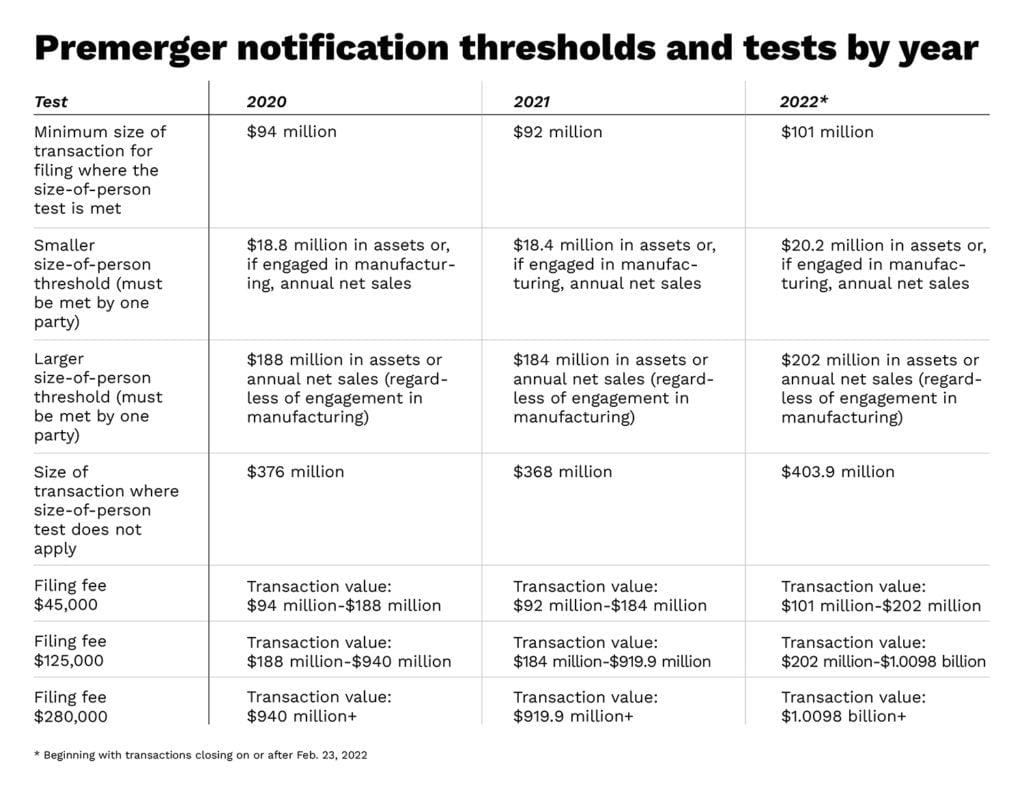

In February 2021, the FTC lowered the HSR premerger notification thresholds for the first time since 2010 as a result of the decline in the gross national product (GNP) in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

What a difference a year makes. Thresholds for 2022, which apply to deals closing on or after Feb. 23, 2022, have increased significantly from their pre-pandemic levels.

While these increases are unlikely to impact larger transactions, they should be viewed as positive news for smaller deals. Notably, the HSR filing fees (which start at $45,000 and top out at $280,000, based on the size of the transaction) have not increased, at least not yet.

While these increases are unlikely to impact larger transactions, they should be viewed as positive news for smaller deals. Notably, the HSR filing fees (which start at $45,000 and top out at $280,000, based on the size of the transaction) have not increased, at least not yet.

The Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act of 2021 is pending in Congress. If enacted, the fees for mega-deals (those valued at $1 billion and over), would increase substantially. For example, a merger valued at $1 billion would pay a $400,000 filing fee, a merger valued at $2 billion would pay an $800,000 filing fee and mergers valued at $5 billion and above would pay a $2.25 million filing fee.

Filing fees would also be subject to annual increases based on the Consumer Price Index. In a concurring statement regarding the 2022 HSR thresholds, FTC Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter stated “[w]e hope that this technical and common-sense change can be quickly approved and enacted.”

More good (but old) news: Electronic filing is (hopefully) here to stay

Regardless of how one views the burdens of HSR compliance, no one can deny that when the pandemic hit and remote work became the norm, the FTC was able to pivot incredibly quickly to an all-electronic filing platform. Gone are the days of bike messengers traversing the halls of the FTC and DOJ to deliver filings and nervous filers worrying about whether their filings made it before the offices closed. In mid-March 2020, the FTC quickly rolled out an electronic filing system with easy-to-understand instructions.

The system appears to have performed extremely well. The FTC also began accepting electronic signatures. Though still referred to as temporary, there is no reason why we should go back to the pre-pandemic days of hard copy filing and wet signatures.

A tidal wave of HSR filings and the consequences: Not all good news

Since the initial decline during the early days of the pandemic, merger and acquisition activity in the United States and worldwide has taken off rapidly. As a result, the number of HSR filings has increased exponentially. Presumably, the lower 2021 HSR thresholds partially contributed to this uptick in filings.

The FTC has described increased M&A activity and resulting HSR filings following the initial slump as an “unprecedented merger wave” that has strained its resources. In response to this extreme increase in filings, in July 2020, the FTC began posting the monthly totals of HSR transactions on a six-month rolling basis on the PNO homepage to supplement the reported monthly HSR transaction numbers in its annual HSR reports published following the end of a fiscal year.

A comparison of the historical number of HSR transactions in November 2019, 2020 and 2021 illustrates how dramatically HSR transactions have risen. November is often the busiest month of the year for HSR filings because many deals close at year-end and most transactions have a 30-day waiting period.

True to this trend, November was the busiest month for HSR filings in each of the past three years examined. In November 2019, the FTC and DOJ were notified of 254 transactions. In comparison, in November 2020, there were 206 transactions. Then, in November 2021, it was a whopping 607 transactions. That’s an increase of more than double between 2019 and 2021.

While the FTC has not published the HSR Act annual report for fiscal year 2021 yet and most likely will not do so until late this year, the preliminary numbers posted on the PNO website indicate that about 4,130 transactions were reported last year. This would be a two-fold increase from the pre-pandemic number of reported transactions in 2019 and over two and a half times the transactions reported in 2020.

This dramatic wave of increased HSR filings will likely continue, albeit at a somewhat slower pace. According to the PNO website, 659 transactions were reported during the first quarter of 2022 compared to 837 during the first quarter of 2021. This is a decrease of 27% year over year but still significantly more than the 428 transactions reported during the first quarter of 2020. As we’ll discuss shortly, the onslaught of HSR filings has stretched the resources of the FTC and DOJ to review HSR filings and has affected the process for reviewing those filings.

‘Temporary’ suspension of early termination may be permanent

In February 2021, the FTC, with the support of the DOJ, announced what was described as a temporary suspension of early termination (ET). This refers to the discretionary practice where the agencies end the waiting period for HSR filings before the allotted 15- or, more commonly, 30-day waiting period. Prior to the suspension of the practice, ET was regularly granted for HSR filings that clearly did not present any antitrust concerns, sometimes in less than two weeks after the filings were made. ET was often relied upon by parties desiring to close more quickly after filing HSR.

Then in March 2021, the agencies announced they would resume granting ET in the limited situation where the FTC or DOJ issues a second request but then determines that the concerns regarding competition are resolved prior to the parties’ certifying substantial compliance with the second request. (A second request allows the agencies to extend their review of the transaction and to obtain additional extensive information from the parties to the proposed transaction. In that scenario, the parties must certify substantial compliance with the second request from the government before they can close. A second request is issued for only a small percentage of the total HSR filings made.)

In the announcement, the agencies stated they would resume the discretionary practice of granting ET when the agencies determine that the competition concerns are resolved prior to the parties certifying substantial compliance with the second request. To date, the FTC has reported only four instances where ET has been granted since its March 12, 2021 announcement, with the most recent occurring on July 21, 2021. Two of the instances appear to relate to the same transaction, and all presumably fall within the limited scope of ET prior to certification of compliance with a second request.

The agencies have not resumed the practice of ET more broadly. While the original announcement of the suspension of ET stated that it would be temporary, we do not expect that grants of ET for competitively benign transactions will resume any time soon because the agencies are likely still overburdened by continued vigorous M&A activity and a resulting number of HSR filings, despite strong criticism from Republican members of the FTC. Therefore, the best practice is to assume the waiting period will be the full 15 or 30 days.

Expiration of the HSR waiting period does not necessarily mean the parties are good to go

Similarly, as we previously noted in more detail, the FTC announced in August 2021 that due to the wave of filings and its limited resources, it would issue pre-consummation warning letters to parties to certain proposed transactions where the initial waiting period is ending, no second request has been issued and an investigation into the transaction has already begun.

Prior to this announcement, it was common for the agencies to have informal communications with the counsel of parties to proposed transactions about which they had concerns, and to use the ability of the parties to pull and refile their HSR filings as a way to extend the time period agencies would review a transaction prior to closing without issuing a second request.

Pre-consummation warning letters provide the federal agencies with another tool when they are not able to get the information needed via informal channels and to suggest a pull-and-refile prior to the expiration of the waiting period. These letters advise that, even though the HSR waiting period is about to expire imminently, the investigation still remains open, so the parties will be closing the transaction at their own risk. The FTC will only send these warning letters where (1) an investigation of a transaction has already begun, and (2) a second request has not been issued. (The pre-consummation warning letter would serve no function where there is a second request.)

The use of pre-consummation warning letters threatens to create significant uncertainty. As warned in the announcement, any party to a transaction who receives such a letter closes at its own risk. Practically speaking, it would be hard to advise a client to move forward with closing until the issues that prompted a warning letter were resolved.

However, while the warning letters would suggest a departure from prior HSR policy, the premise is nothing new. The FTC and DOJ have always had the power to investigate and challenge transactions, even after the transactions have already closed and even if an HSR filing was not required in the first place. Moreover, we anticipate the agencies will continue to contact counsel for parties informally about their potential concerns regarding a proposed transaction during the initial HSR waiting period, and that the receipt of a pre-consummation warning letter should not come as a complete surprise. It is possible that, along with the use of warning letters, there will be more use of the pull-and-refile process.

To date, the use of pre-consummation warning letters appears to have served more as a reminder of the long-standing possibility that federal antitrust agencies could challenge a transaction post-closing rather than a sign that the FTC and DOJ are now actually bringing more challenges to transactions post-closing. We have not seen any indication of a significant uptick in post-closing challenges to transactions, nor do we expect to see such an uptick given several factors.

First, it is much easier and less cumbersome for the agencies to challenge a transaction on the front-end through the HSR review process than to unwind a transaction that has already closed. Second, the agencies have significant leverage to get concessions from the parties to a proposed transaction to make adjustments to resolve anti-competitive concerns. This leverage disappears when a transaction is challenged post-closing. Third, the resources of the agencies have been stretched thin. However, we are continuing to monitor the use of pre-consummation warning letters and the extent to which the federal antitrust enforcement agencies challenge completed transactions.

Treatment of debt and use of informal interpretations

Adding another layer of complexity is an Aug. 26, 2021, blog post by Holly Vedova, then-acting director and now permanent director of the FTC Bureau of Competition. This blog post suggested a reversal of the FTC’s long-held position regarding debt to be retired when determining the size of transaction for HSR reportability. This blog post also casts doubt on counsel’s ability to rely on informal interpretations posted to the PNO website when analyzing the reportability of proposed transactions.

Debt

Prior to the post, the FTC had long excluded the value of the debt of the target owed to third parties and noncorporate debt to be paid off as part of the transaction when calculating the size of transaction for acquisitions of voting securities and noncorporate interests. (This prior position regarding debt did not apply when calculating the size of transaction for the acquisitions of assets. Similarly, debt to be assumed by the buyer was also previously included when calculating the size of transaction.)

This meant, for example, that if the total consideration to be paid for a target carrying $60 million in debt was $150 million, then the $60 million debt to be retired would be subtracted from the $150 million purchase price. As a result, the transaction size would be $90 million, below the $92 million size-of-transaction threshold in place when the blog post was published, and no HSR filing would be required. Underpinning this position was the idea that the sellers would not receive the $60 million used to retire the debt and thus would really only owe the $90 million for the sale.

In the blog post, the FTC abruptly changed course and stated that effective Sept. 27, 2021: “the Bureau will begin to recommend enforcement action for companies that fail to file when retirement of debt is part of the consideration for the deal.” The blog post acknowledged that “not all debt retired as a part of a proposed transaction is a consideration” but noted: “sometimes the retirement of debt is part of the consideration for a transaction in that it benefits the selling shareholder(s).” Effective Sept. 27, 2021: “the full or partial retirement of debt should be included in calculating the acquisition price in any instance where selling shareholder(s) benefit from the retirement of that debt.” The FTC has not issued further guidance on this topic since then.

This change of position appears to be grounded in concerns about the possible improper use of debt payoffs to avoid HSR reportability. Such a situation might occur where a target took on debt immediately prior to the proposed transaction so the value of the debt retired would be excluded from the acquisition value. As this misuse of debt is already forbidden by the prohibition against transactions or devices for avoidance in 16 C.F.R. § 801.90, and we are not aware of any enforcement actions where debt was misused in this way to avoid a filing, it is unclear why the FTC decided this additional change in position was necessary.

Nonetheless, parties to transactions in which debt of the target will be retired as part of the acquisition need to proceed with caution when determining the size of the transaction. While every situation must be analyzed individually, as a general proposition, the safest, most conservative course is to include all debt to be retired when the retirement of that debt could in some way benefit the sellers, especially if the debt was acquired close in time to the transaction.

Informal interpretations

The blog post also put in question the reliability of the informal interpretations from the PNO, which, although never having the force of law, have been long relied upon by HSR practitioners, entities engaged in mergers and acquisitions and their advisors. This guidance has long been an invaluable tool for practitioners. Presumably, informal interpretations were also useful to the PNO staff to reduce time they spend answering the same questions repeatedly.

In outlining issues with the use of informal interpretations, the blog post noted: “[th]ese informal interpretations are not reviewed or authorized by the Commission, and do not carry the force of law.” It expressed concerns that parties to transactions may improperly rely upon the informal interpretations in place of conducting their own legal analysis and noted at least one informal interpretation which concerned the treatment of debt, “missed the mark.” Accordingly, “[t]he Bureau is concerned that some of these informal interpretations may not reflect modern market realities or the policy position of the Commission. We are currently in the process of reviewing the voluminous log of informal interpretations to determine the best path forward.” Notably, even before the August 26, 2021, blog post, the PNO annotated some informal interpretations that no longer reflected the PNO’s views, and they also maintain a list of “Superseded Informal Interpretations” on the PNO’s website.

What this means going forward — whether any informal guidance from the PNO can reasonably be relied upon — remains unclear. The informal interpretations are still published to the PNO website, but the most recent one available predates the August 2021 blog post.

Aggressive antitrust enforcement emphasis of the Biden Administration, the antitrust enforcement agencies and some members of Congress

Along with the changes to the HSR review process created by the Covid-19 pandemic are the developments that accompanied the change in presidential administrations. As is typical when there is a new administration, President Joe Biden has ushered in new priorities for the federal government agencies. These priorities include a strong emphasis on aggressive antitrust enforcement.

In July 2021, Biden issued an executive order on antitrust policy. This EO affirmed the commitment of the Biden Administration to enforce existing antitrust laws and re-affirmed the enforcement authority of the federal government under the existing laws:

… it is the policy of my Administration to enforce the antitrust laws to combat the excessive concentration of industry, the abuses of market power, and the harmful effects of monopoly and monopsony — especially as these issues arise in labor markets, agricultural markets, Internet platform industries, healthcare markets (including insurance, hospital, and prescription drug markets), repair markets, and United States markets directly affected by foreign cartel activity.

It is also the policy of my Administration to enforce the antitrust laws to meet the challenges posed by new industries and technologies, including the rise of the dominant Internet platforms, especially as they stem from serial mergers, the acquisition of nascent competitors, the aggregation of data, unfair competition in attention markets, the surveillance of users, and the presence of network effects.

While it did not announce plans for new antitrust legislation or regulations, the EO makes it clear that the Biden Administration intends to have a much more robust view and enforcement of the existing antitrust law than recent administrations. Moreover, rather than limiting competition policy to the FTC and DOJ as is tradition, the Biden Administration is taking a whole-government approach involving other federal agencies and a council at the White House. This stance has found bipartisan support from Congress, with Democratic and Republican co-sponsored bills that could change and expand antitrust law circulating through Congress.

DOJ is Using Existing Antitrust Law in Aggressive and Unconventional Ways. Compliance and the Board Should Take Stock.

Recent aggressive antitrust enforcement activity from the DOJ warrants re-evaluating whether existing corporate compliance programs adequately address organizational and individual...

Read moreDetailsA September 2021 Competition Matters blog post by Vedova highlights the ramped-up approach of the FTC to merger review and enforcement by outlining a more stringent second review process. A second request is issued if, after HSR filing is made, the DOJ or FTC decides that it requires more information to evaluate the potential anticompetitive effects of the proposed transaction. In that case, the agency issues a second request for a substantial amount of information, documents and data from the parties to the transaction. The HSR waiting period is extended beyond the initial 15 or 30 days until both parties to the transaction are in substantial compliance with the second request. The blog post outlined changes to how the FTC would handle second requests, which broadly speaking, include the following:

- Second requests might be more holistic and consider additional factors of market competition that were not previously considered.

- The FTC adjusted certain practices — such as the consideration of requests for modification, e-discovery and privilege logs — to be aligned with DOJ practices.

- The FTC made second requests and other requests for information available to all commissioners and relevant agency officers rather than just the FTC chair.

Remarks delivered in January 2022 by Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter of the DOJ’s Antitrust Division provided a preview into how the DOJ would carry out this more aggressive antitrust enforcement approach. Kanter noted the need to modernize Section 2 of the Sherman Act doctrine, the merger review guidelines and remedies for antitrust violations to be responsive to and appropriate for the realities of the modern markets. To that end, with respect to remedies, Kanter noted his general distaste for settlements and divestitures, previously commonplace in antitrust enforcement actions, as being ineffective to protect and restore competition.

Antitrust Chief Outlines Aggressive Approach to Enforcement in Digital Markets

The DOJ’s new enforcement chief is signaling an aggressive approach to competition in digital markets. Compliance expert Michael Volkov warns...

Read moreDetailsMoreover, both the DOJ and FTC have turned a more critical eye to antitrust enforcement in labor markets over the past several years. For example, during 2021, the agencies conducted joint workshops and solicited comments regarding labor protections in merger enforcement. The DOJ also brought criminal cases for no-poach agreements and wage collusion. This heightened attention on the impact of transactions on labor markets is unlikely to wane. As a result, counsel should pay careful attention to non-compete clauses and related provisions as they draft and negotiate merger agreements.

A willingness to bring criminal cases under Section 2 of the Sherman Act further signals a departure from the prior approach taken by the DOJ, which has not brought a criminal monopolization case in many years, and a turn to a significantly more aggressive approach. To our knowledge, the DOJ last brought a criminal case for monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy to monopolize in 1977, almost a half-century ago. See United States v. Braniff Airways, Inc., 453 F. Supp. 724 (W.D. Tex. 1978).

Democrats in Congress have introduced a slate of bills aimed at antitrust reform and enforcement. Perhaps most notable of those is the bill introduced in March 2022 by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Mondaire Jones (D-N.Y.). The bill, Prohibiting Anticompetitive Mergers Act of 2022, would prohibit mergers and acquisitions valued at over $5 billion, would result in market shares above 33% for sellers or 25% for employers and would result in highly concentrated markets under the 1992 Merger Guidelines issued by the DOJ and FTC among other changes.

Reflecting this robust approach and the focus outlined in the EO are recent actions brought by the FTC to block proposed mergers under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18. For example in June 2022, the FTC announced that it was bringing two sets of administrative complaints and federal lawsuits to block mergers between rival healthcare systems on the grounds that the proposed transactions would eliminate head-to-head competition between the healthcare providers, increase market concentration and substantially lessen competition and result in fewer, less attractive alternatives for insurers.

One action sought to prevent the proposed merger of two Utah healthcare systems where the proposed transaction would eliminate two of the four largest healthcare systems in the region where approximately 80% of Utah residents live. The other sought to prevent the acquisition of a competing healthcare system by one of the largest hospital systems in New Jersey.

The approach signaled by the EO, which is being implemented by the antitrust agencies and has support from some in Congress, could result in more scrutiny of HSR filings for proposed transactions, particularly transactions where there is horizontal or vertical overlap between the parties. Additionally, when looking at the combination of the EO with the suspension of ET and the use of pre-consummation warning letters, parties to transactions covered by the HSR, particularly those where the buyer is a strategic one, would be well served by allowing ample runway between the HSR filing date and desired closing date to allow time for potential increased scrutiny.

Examples of more robust antitrust enforcement: DaVita, JAB

The commitment to robust antitrust enforcement was recently made clear in a January, 2022 decision and order issued by the FTC concerning DaVita and its wholly owned subsidiary Total Renal Care. Following a public comment period, the FTC approved the final order, settling charges that the acquisition of the dialysis clinics of the University of Utah Healthy by DaVita would reduce competition for outpatient dialysis in the Provo, Utah market. The order not only required DaVita to divest three dialysis clinics in the Provo area and prohibited DaVita from entering or enforcing employee restrictions, including non-compete agreements, but also required DaVita to obtain prior approval from the FTC before acquiring any new ownership interest in any dialysis clinic in the entire state of Utah for a decade.

This final order dovetails with the FTC’s July 2021 vote to rescind its 1995 policy statement concerning prior approval and prior notice provisions in merger cases, which had ended the FTC’s prior practice of requiring parties that previously proposed transactions in violation of antitrust laws to obtain prior approval by the FTC for proposed future transactions. An FTC news release regarding the vote to rescind the policy noted that the 1995 policy statement deprived the FTC of a “valuable law enforcement tool” and required the commission to re-review and re-litigate similar problematic transactions involving the same parties while costing valuable funds and manpower. The statement positioned the vote as providing the FTC with an efficient, effective enforcement tool to stop “repeat offenders.”

The FTC recently went even further in a consent order regarding the proposed acquisition of a veterinary clinic company by JAB Consumer Partners, a private equity fund whose holdings include pet care and pet services. The proposed transaction would have combined its existing holdings with those of the target to form an entity controlling nearly 100 specialty and emergency clinics through the United States.

In addition to requiring prior notice and approval of acquisitions of specialty and emergency veterinary clinics located within 25 miles of any JAB states in the markets where the proposed transaction might illegally lessen competition, the consent order also requires JAB to provide advance written notice to the FTC of proposed acquisitions of any specialty or emergency veterinary clinic within 25 miles of any current or future JAB clinic anywhere in the United States, not just the impacted markets.

For the parties affected, which include those that have entered a consent order with the FTC to settle allegations that a merger was anticompetitive and violated the antitrust laws, this shift in FTC protocol interjects uncertainty into any merger activity they may wish to pursue. Regardless of how unproblematic the proposed merger may be, the parties now need to account for possible additional time for FTC review and approval, as well as the possibility that the FTC will not approve the transaction.

At the moment, only the FTC is requiring prior approval for “repeat offenders.” It remains to be seen if the Antitrust Division of the DOJ will also adopt this tool. Regardless, the FTC’s decision to rescind the prior-approval requirement is yet another indicator of the aggressive antitrust enforcement approach taken by most agencies.

Conclusion

Taken together, these developments clearly signal the federal government is looking at proposed transactions more carefully and that entities engaged in mergers and acquisitions — even ones where the businesses of the acquiring and acquired parties do not overlap at all — should expect longer turnaround times for HSR review. Gone are the days of ET requests being granted in two weeks or less and of a perceived more lenient approach to proposed transactions. We do not expect this to change any time soon. Now, more than ever, parties to proposed transactions need to be careful that they fully understand HSR reporting requirements and potential antitrust trigger points.

Carrie Hanger is a partner at Nelson Mullins, where her practice focuses on healthcare law, biosciences and antitrust. In her healthcare law and biosciences practice, she assists healthcare systems, surgical centers, physician groups, long–term care facilities, hospices, home health providers, and entities engaged in the clinical research across the State of North Carolina and beyond. Carrie’s antitrust experience covers a variety of industries with a particular focus on healthcare antitrust matters.

Carrie Hanger is a partner at Nelson Mullins, where her practice focuses on healthcare law, biosciences and antitrust. In her healthcare law and biosciences practice, she assists healthcare systems, surgical centers, physician groups, long–term care facilities, hospices, home health providers, and entities engaged in the clinical research across the State of North Carolina and beyond. Carrie’s antitrust experience covers a variety of industries with a particular focus on healthcare antitrust matters.