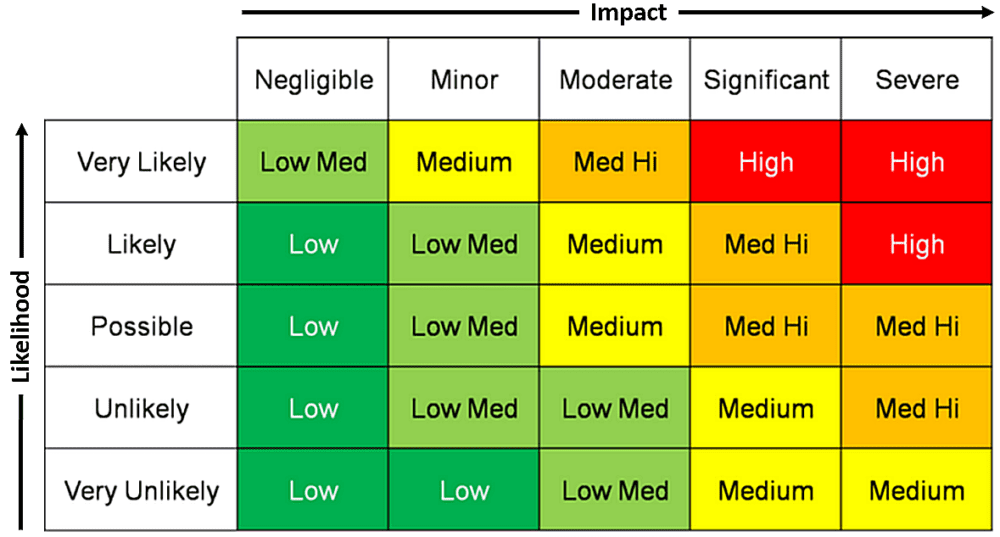

While heatmaps (or risk matrices) are still considered one of the most popular tools for risk assessment, plenty of research has brought to light their various methodological and psychological limitations; they may actually lead to worse decisions than doing no risk analysis at all. Alex Sidorenko outlines the alternatives.

OK, the title is obviously a joke, because the alternatives (multiple) have been available to anyone willing to learn for over 50 years. But since you clicked, this article will probably change your life for the better.

Wait, do we even need an alternative?

To me, using risk matrices is a question of ethics and professional skills, and it is totally up to the individual risk manager. In that sense, risk matrices are like horoscopes (more in Douglas Hubbard‘s book, “The Failure of Risk Management: Why It’s Broken and How to Fix It”): They are fun, they are easy to understand and they are everywhere, but you probably wouldn’t use them for any meaningful day-to-day life decision – or if you did, you would have the decency to realize it’s no better than a coin toss, and you definitely wouldn’t talk about it at the conferences, calling it best practice.

The flaws are fundamental to the design of risk matrices, and there nothing a risk manager or business analyst can do to make them reliable. All these flaws have been discussed here, in this video by Osama Salah, in this post by David Vose and in dozens of posts I have been making over the years. Additionally, research by Tony Cox and Douglas Hubbard has shown that risk matrices consistently perform worse at measuring and communicating risks than proper quantitative tools.

So what are the alternatives? There are plenty, but for the tool to be any better, the following criteria have to be fulfilled:

- Risk analysis has to be performed at the time of decision-making, not once a quarter.

- The results of risk analysis should not be expressed as arbitrary risk levels, but rather as volatility or range or scenarios of the decision/objective itself (with some exceptions; in HSE, for example).

- The output of risk analysis should have a direct and immediate impact on the decision at hand.

It is also very important to distinguish between two types of risk analysis techniques:

- Techniques to better understand the nature of riskto make a decision how to manage it. Usually used when a specific risk is known and significant and management needs to deal with it in a cost-effective manner. These include bow-tie diagrams; FMEA/FMECA; HAZID, HAZMAT and HAZAN; the 5 whys; influence diagrams; and ICAM, etc.

- Techniques to better understand how uncertainty affects the decision or objective.Used when making a decision and preparing or approving a strategy, budget, forecast, long-term pricing, etc. and when the risks are not obvious. These include scoring, decision trees, sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis, stress testing and various simulation techniques (agent-based, system dynamics, discrete event).

The application of the techniques above will also depend on the decision complexity, materiality, level of uncertainty and the time and resources available to risk manager:

For Simple Decisions

By far the easiest and the most common way to assign risk to an entity, project, supplier, business unit or piece of equipment is by using a scoring methodology. In fact it is so common that hundreds of companies have been using it without calling it risk management forever:

- S&P, Moodys, Fitch rating agencies to assign ratings to companies

- Procurement departments to rank existing suppliers (gold, silver, bronze or blacklisting them)

- Classifying spare parts or pieces of equipment based on criticality, etc.

- Banks and corporations to allocate debtors to risk buckets/categories or to classify bad debtors

- Firefighters classifying buildings into fire risk categories, etc.

Basically, any type of methodology that allows the grading/categorizing of items based on their predetermined characteristics is a better way to communicate risks and to use that information for decision-making. Sometimes it could look like a very simple checklist.

For Decisions on How to Mitigate a Particular Risk

If you are in the situation where you need to determine the best ways to mitigate a specific kind of risk, then a bow-tie diagram or an influence diagram will be very helpful. There are a bunch of techniques that help to visualize the risk by breaking it into components – for example, causes and consequences, as is the case with bow-ties.

This is very helpful to switch on system 2 thinking and to overcome at least some of the cognitive biases. The bow-ties are pretty basic and should be in every risk managers arsenal. FMEA, FMECA, fault trees, 5 whys and ICAM investigation techniques are very similar in principle. Their main objective is to write down possible components of a risk, reminding us not to forget important sources or consequences, even though they may not be obvious at first.

I used bow-ties a lot; once I was even childish enough to present it to the CEO (ex-deputy Prime Minister of the country). That obviously didn’t go down well. So, it’s probably best to use them as internal analysis tools rather than a communication tool. My personal secret with bow-ties is to always have at least seven causes and seven consequences and at least three second-level causes and consequences on each branch. That way, we definitely switch from S1 to S2 and improve our chances of finding a solution.

For Any Decision Involving Numbers (Wait, That’s Most of Them)

For the rest of the cases, it is actually more important for us not to understand the significance of each individual risk but rather how uncertainty in general affects our decision, KPI or objective. Nassim Taleb calls it f(x). They also call it f(x) in operations research. That means we should be more interested in the effect of risk on something rather than the level of risk itself.

To my surprise, the message above is actually very difficult (almost impossible) for the risk managers to digest.

This is what I call risk management 2 – using risk analysis as a decision-making tool. Since the idea to use risk management as a decision-making tool is much older than the idea to use risk management as an element of corporate governance, all we need to do is to open any good book on decision science or probability theory to find the tools.

Let’s repeat. Here are just some of the common techniques – some more than 50 years old – ranked from simple to difficult:

- Decision trees or influence diagrams

- Scenario analysis

- Stress testing

- Simulation modeling techniques

The irony is that while many risk management departments have been using heatmaps to rank risks, other business units have been using proper risk analysis techniques forever without calling it risk management. Doctors have been using decision trees; investment professionals using sensitivity analysis; finance using scenarios; and pharma companies, geologists and weather forecasters using simulation modelling forever.

For Big and Important Decisions

This one is simple: If the decision is complex and the stakes are high, use simulation modelling or better.

*Author’s note: Thank you Damir Ramazanov, Group Project Risk Manager, ERG for helping with the article and providing quality review.

This article was originally shared on the Risk Academy blog and is republished here with permission.

Alex Sidorenko is a risk expert with over 15 years of private equity, sovereign wealth fund risk management experience across Australia, Russia, Poland and Kazakhstan. In 2014, Alex was named the Risk Manager of the Year by the Russian Risk Management Association.

As a VP at the Institute for Strategic Risk Analysis in Decision Making, Alex is responsible for risk management consulting, training and certification across Russia and CIS. Alex is the co-author of the global PwC risk management methodology, the author of the risk management guidelines for SME (Russian standardization organization), risk management textbook (Russian Ministry of Finance), risk management guide (Australian Stock Exchange) and the award-winning training course on risk management (Best Risk Education Program 2013, 2014 and 2015).

Alex Sidorenko is a risk expert with over 15 years of private equity, sovereign wealth fund risk management experience across Australia, Russia, Poland and Kazakhstan. In 2014, Alex was named the Risk Manager of the Year by the Russian Risk Management Association.

As a VP at the Institute for Strategic Risk Analysis in Decision Making, Alex is responsible for risk management consulting, training and certification across Russia and CIS. Alex is the co-author of the global PwC risk management methodology, the author of the risk management guidelines for SME (Russian standardization organization), risk management textbook (Russian Ministry of Finance), risk management guide (Australian Stock Exchange) and the award-winning training course on risk management (Best Risk Education Program 2013, 2014 and 2015).