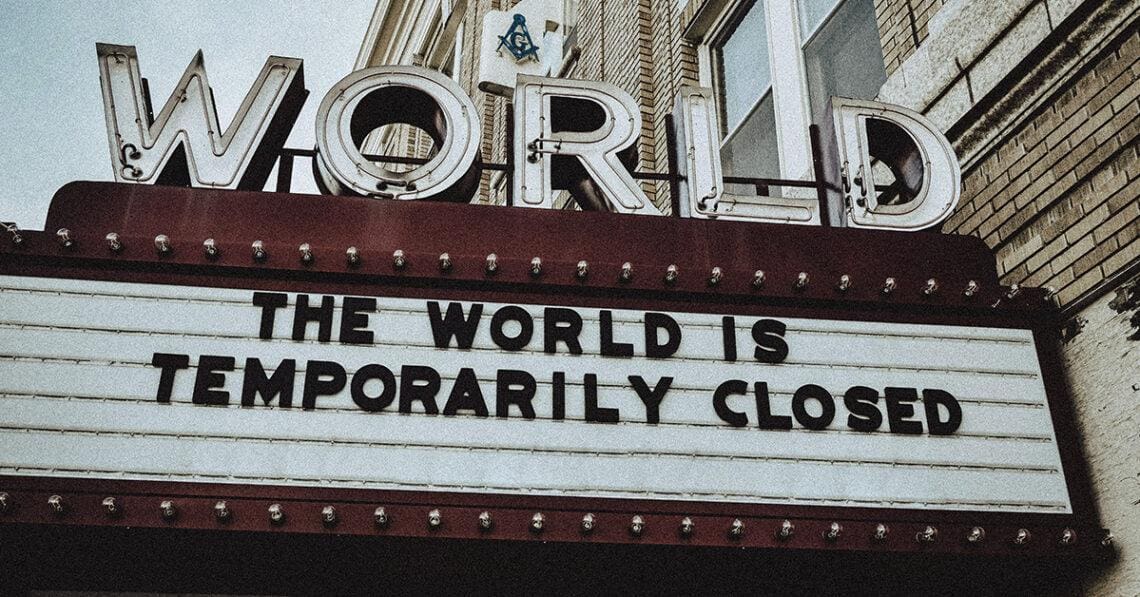

Force majeure provisions in contracts haven’t garnered much attention over the years. But the Covid-19 pandemic appears to have changed that. Attorneys Gretchen L. Jankowski and Jacqueline M. Weyand explore how courts have come down on whether pandemic disruptions are considered acts of God.

Before Covid-19, force majeure provisions received little attention during contract negotiations and even less attention by the courts. Generally speaking, a force majeure clause in a contract excuses a party’s failure to perform when non-performance is outside of the party’s reasonable control.

Force majeure provisions allocate risk for unforeseeable events. A typical pre-pandemic force majeure provision looked something like this:

“The failure of either party to perform any obligation under this contract shall not be deemed to be a default provided such failure is, and continues to be, the result of force majeure. As used herein ‘force majeure’ shall mean any delay which arises from or through strikes, lockouts, labor difficulty, explosion, sabotage, riot, civil commotion, act of war, or other causes beyond the control of such non-performing party.”

During the 10-year period before the pandemic, there were fewer than 500 decisions in federal courts addressing the defense of force majeure to avoid performance of a contract, according to our analysis. Of those cases, none addressed the applicability of force majeure to a pandemic or even a national health crisis.

In fact, one of the few cases addressing the impact of a national health crisis within the context of a force majeure provision dates back to the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918. The court in Citrus Soap Co. v. Peet Brothers Manufacturing Co. held that a delay in performance was excused by the parties’ “contingency of delay” contract provision.

In the three years since the World Health Organization declared Covid a pandemic, there have been hundreds of cases asking courts to determine whether a pandemic qualifies as a force majeure event across myriad industries, including aviation, coal and commercial leasing. These cases were brought largely because a force majeure provision did not contain explicit language detailing a pandemic or national health crisis, and courts often took a narrow view, finding that a force majeure event did not occur.

No Need to Scream: How to Protect Your Business in the Face of the FTC’s Proposed Noncompete Ban

The FTC has a plan it says would empower workers with an additional $300 billion in wages per year. While the proposal remains in the public-comments phase, corporate America has already begun chiming in, with most business leaders criticizing the proposal.

Read moreWhat these cases have shown is that a litigant’s success (or lack thereof) in enforcing a force majeure provision often turns on specificity. Where the pandemic was considered a force majeure event, the force majeure provision included phrases like “epidemics” or “[an]other occurrence which is beyond the control of the parties.” In contrast, common terminology like an “act of God” or general catch-all language might not be specific enough.

Fast-forward to today. We are starting to see force majeure provisions with more specificity. By way of example, consider this force majeure provision (emphasis added):

“Neither Party will be liable for any failure or delay in performing an obligation under this Agreement that is due to any of the following causes (which causes are hereinafter referred to as ‘Force Majeure’), to the extent beyond its reasonable control: acts of God, accident, riots, war, terrorist act, epidemic, pandemic (including the Covid-19 pandemic), quarantine, civil commotion, breakdown of communication facilities, breakdown of web host, breakdown of internet service provider, natural catastrophes, governmental acts or omissions, changes in laws or regulations, national strikes, fire, explosion, or generalized lack of availability of raw materials or energy.”

Including a robust force majeure provision goes a long way in appropriately allocating risk between the parties for unforeseeable events. Robustness can be achieved not only by expanding the list of events but also by drafting the language to ensure that the list is illustrative and not exhaustive.

An illustrative list containing the words “including, without limitation,” can greatly expand the scope of what can be categorized as a force majeure event, while a restrictive list will ensure that only those force majeure events listed will qualify. If a force majeure event occurs, performance under the terms of the agreement can be excused in whole or in part. In some cases, performance will only be excused for the specific period of time that the force majeure event impacts the business. Parties should also be clear about the type and substance of the notice that will be required if a force majeure event occurs.

While Covid-19 litigation continues to make its way through the courts, decided cases highlight some of the issues surrounding force majeure provisions. The case of JN Contemporary Art LLC v. Phillips Auctioneers LLC is instructive as to how a force majeure event can result in the termination of an agreement. In JN Contemporary Art, Phillips agreed to sell a painting on behalf of JN Contemporary at an auction scheduled for March 2020. Based upon the Covid-19 restrictions issued by the governor of New York, Phillips invoked the force majeure clause to terminate the agreement. JN Contemporary filed a lawsuit in district court for breach of contract, which was dismissed on the grounds that the pandemic constituted a circumstance beyond the parties’ reasonable control under the force majeure provision. On appeal to the Second Circuit, the court affirmed the district court’s decision and held that the Covid-19 pandemic qualified as a force majeure event under the terms of the parties’ agreement, so Philips had the right to terminate the agreement.

However, other courts have held that the Covid-19 pandemic was entirely foreseeable and have refused to release parties from their contractual obligations. In Regal Entertainment Group, a Delaware court rejected the invocation of the force majeure clause and found that the Covid-19 pandemic was “neither unprecedented nor unforeseeable.” Referencing both the Spanish Flu in the early 20th century and the Writers Guild strike in 1988, the court reasoned that the two sophisticated business parties should have foreseen the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has demonstrated that force majeure provisions should not be an afterthought. Instead, businesses should review their current force majeure provisions and determine whether they contain sufficient specificity to excuse nonperformance.

Gretchen L. Jankowski

Gretchen L. Jankowski Jacqueline M. Weyand

Jacqueline M. Weyand