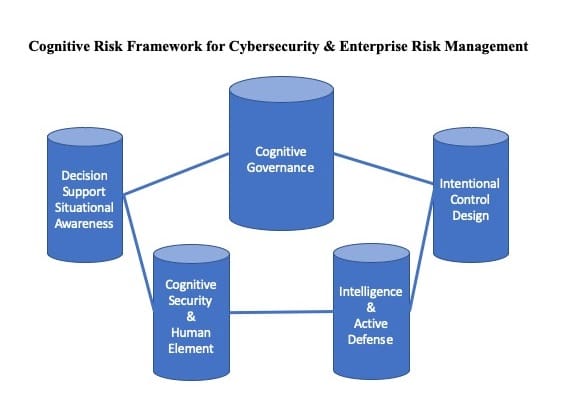

James Bone explores cognitive governance, the first pillar of the cognitive risk framework, and the five principles that drive the framework to simplify risk governance, add new rigor to risk assessment and empower every level of the organization with situational awareness to manage risk with the right tools.

The three lines of defense (3LoD), or more specifically, risk governance is being rethought on both sides of the Atlantic.[1],[2],[3] A 3LoD model assigns three or more defensive lines of accountability to protect an organization in the same vein as Maginot’s Lines of Defense to defend Verdun.[4] IT security also adopted layered security and controls, but is now evolving to incorporate risk governance approaches. The Maginot Line was considered state of the art for defensive wars fought in trenches, yet vulnerable to offensive change in enemy strategy. Inflexibility in risk practice design and execution is the Achilles’ heel of good risk governance. In order to build risk programs that are responsive to change, we must redesign the solutions we are seeking in risk governance.

A cognitive risk framework clarifies risk governance and provides a pathway for organizations to understand and address risks that matter. There are many reasons 3LoD is perceived to not meet expectations, but a prominent one is unresolved conflicts in perceptions of risk …. the human element.[5] Unresolved conflicts about risk undermine good risk governance, trust and communication.

In Risk Perceptions, Paul Slovic reflected on interpersonal conflicts: “Can an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect be created among opposing parties? How can we design an environment in which effective, multiway communication, constructive debate and compromise take place?”[6]

A cognitive risk framework is designed to find simple solutions to risk management through a focus on empowering the human element. Please keep this perspective in mind as you digest the five principles of cognitive governance.

Principle #1: Risk Governance

Principle #1: Risk Governance

Risk governance continues to be a concept that is hard to grasp and elusive to define in concrete terms. Attributes of risk governance such as corporate culture, risk appetite and strategy are assumed outcomes, but what are the right inputs to facilitate these behaviors? Good risk governance is sustainable through simplicity and design. In an attempt to simplify risk governance two inputs are offered: discovery and mitigation.

Risk governance is presented here as two separate and distinct processes:

Risk Assessment (Discovery) and Risk Management (Mitigation)

Risk management is often conflated to include risk assessment, but the skills, tools and responsibility to adequately address these two processes require risk governance to be separate and distinct functions. This may appear to be counterintuitive at first glance, but too narrow a focus on either the mitigation of risk (management) or the discovery of risk (assessment) limit the full spectrum of opportunities to enhance risk governance.

Why change?

Risk analysis is a continuous process of learning and discovery inclusive of quantitative and qualitative methods that reflect the complexity of risks facing all organizations. Risk analysis should be multidisciplinary in practice, borrowing from a variety of analytical methodologies. For this reason, a specialized team of diverse risk analysts might include data scientists, mathematicians, computer scientists (hackers), network engineers and architects, forensic accountants and other nontraditional disciplines alongside traditional risk professionals. The skill set mix is illustrative, but the design of the team should be driven by senior management to create situational awareness and the tools needed to analyze complex risks. More on this point in future installments.

This approach is not unique or radical. NASA routinely leverages different risk disciplines in preparation for space travel. Wall Street has assimilated physicists from the natural sciences with finance professionals, mathematicians and computer programmers to build risk solutions for their clients and to manage their own risk capital. Examples are plentiful in automotive design, aerospace and other high-risk industries. Success can be designed, but solving complex issues requires human input.

“Risk analysis is a political enterprise as well as a scientific one, and public perceptions of risk play an important role in risk analysis, adding issues of values, process, power and trust to the quantification issues typically considered by risk assessment professionals (Slovic, 1999)”.[7]

Separately, risk management is the responsibility of the board, senior management, audit and compliance. Risk management is equivalent to risk appetite, which is the purview of management to accept or reject. Senior executives are empowered by stakeholders inside and outside the firm to selectively choose among the risks that optimize performance and avoid the risks that hinder. Traditional risk managers are seldom empowered with these dual mandates, and I don’t suggest they should be.

In other words, risk management is the process of selecting among issues of value, power, process and trust in the validation of issues related to risk assessment. To actualize the benefits of sustainable risk governance, advanced risk practice must include expertise in discovery and mitigation. Organizations that develop deep knowledge in both disciplines and master conflicts in perceptions of risk will be better positioned for long-term success.

Experienced risk professionals understand that without the proper tone at the top, even the best risk management programs will fail.[8] Tone at the top implies full engagement by senior executives in the risk management process as laid out in cognitive governance.[9] Developing enhanced risk assessment processes builds confidence in risk-management decisions through greater rigor in risk analysis and recommendations to improve operational efficiency.[10] Risk governance (Principle #1) transforms assurance through perpetual risk-learning.

Principle #2, perceptions of risk, provides an understanding of how to mitigate the conflicts that hurt cognitive governance.

Principle #2: Perceptions of Risk

Risk should be a topic upon which we all agree, but it has become a four-letter word with such divergent meanings that a Google search results in 232 million derivations! The mere mention of climate change, gun control or any number of social or political issues instantly creates a dividing line that is hard, if not impossible, to penetrate. Many of these conflicts are based on deeply held personal and political beliefs that are intractable even in the face of science, data or facts, so how does an organization find common ground?

In discussing this issue with a chief operations officer at a major international bank, I was told, “we thought we understood risk management until the bank almost failed in the 2008 Great Recession.” The truth is, most organizations are reluctant to speak honestly about risks until it is too late or only after a “near miss.” In other words, risk is an abstract concept until we experience it firsthand.[11] As a result, each of us bring our own unique experience of risk into any discussion that involves the possibility of failure. These unresolved conflicts of perceptions of risk create friction in organizations, causing blind spots that expose firms to potential failure, large and small.

But why is perception of risk important?

Each of us bring a different set of personal values and perspectives to the topic of risk. This partly explains why sales people view risks differently than say, accountants; risk is personal and situational to the people and circumstances involved. The vast majority of these conflicting perceptions of risk are well-managed, but many are seldom fully resolved, leading to conflicts that impede performance.

Risk professionals must become attuned to and listen for these conflicts, because they represent signals about risk. Perceptions of risk represent how most people feel about a risk, inclusive of positive or negative outcomes from their own experience. Researchers view risk as probability analysis. Understanding and reconciling these conflicts in perceptions of “risk as feelings” and “risk as analysis” is a low-cost solution that releases the potential for greater performance. Yet the devil in the details can only be fully uncovered through a process of discovery.

Principle #1 (risk governance) acts as a vehicle for learning about risks that enlightens principle #2 (perceptions of risk). Even the most seasoned executive is prone to errors in judgment as complexity grows. However, communications about risk are challenging when we lack agreed-upon procedures to reconcile these conflicts.

Albert Einstein provided a simple explanation:

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

He knew the difference requires a process that creates an openness to learning.

Principle #1 (risk governance) formalizes continuous learning about risks in order to avoid analysis paralysis in decision-making. Risk governance focuses on building risk intelligence. Principle #2 (perceptions of risk) leverages risk intelligence to fill in the gaps data alone cannot.

Perceptions of risk are complex, because they are seldom expressed through verbal behavior. In other words, how we act under pressure is more powerful than mission statements or even codes of ethics![12] We say we are safe drivers, but we still text and drive. People take shortcuts when their jobs become too complex, leading to risky behavior.[13] Unknowingly, organizations are incentivizing the wrong behaviors by not fully considering the impacts on human factors.

Surprisingly, cognitive governance means fewer, simple rules instead of more policies and procedures. Risk intelligence narrows the “boil the ocean” approach to risk governance. The vast majority of risk programs spend 85 to 95 percent of 3LoD resources on known risks, leaving the biggest potential exposure, uncertainty, unaddressed.

Again, risk governance is about learning what the organization really values and why.

Organizations must begin to re-design the inputs to risk governance. The common denominator in all organizations is the human element, yet its impact is discounted in risk governance.

Principle #3: Human Element Design

A Ph.D. computer scientist friend from Norway once told me that organizations have a natural rhythm, like a heartbeat, and that cyber criminals understand and leverage this to plan their attacks.[14] Busy, distracted and stressed-out workers are generally more vulnerable to cyberattack. No amount of controls, training, punishment or incentives to prevent phishing attacks or other social engineering schemes is effective in poorly designed work environments, including the C-suite and rank-and-file security professionals.[15]

Cyber criminals understand the human element better than all risk professionals!

Human element design is an innovation in risk governance. Regulators have also begun to include behavioral factors, such as conduct risk, ethics and enhanced governance in regulation, but thus far, the focus is primarily on ensuring good customer outcomes. Sustainable risk governance must consider human factors a tool to increase productivity and reduce risk.[16],[17]

Human element design is evolving to address correlations and corrective actions in human factors and workplace errors, information security and operational risk.[18],[19],[20],[21],[22] Principles #1 (risk governance) and #2 (perceptions of risk) assist principle #3 (human element design) in defining areas of opportunity to increase efficient operations and reduce risk in human factors.

Decades of research in human factors in the workplace has led to productivity gains and reductions in operational risk across many industries. We take for granted declining injury rates in the auto and airline industries attributed to human factors design. Simple changes, such as seatbelts and navigation systems in cars and pilot to co-pilot communications during take-offs and landings are just as important – if not more so – as automation and big data projects.

So, why is it important to focus on the human element more broadly now?

The primary reason to focus on the human element now is because technology has become pervasive in everything we do today. Legacy systems, outsourcing, connected devices and networked applications increase complexity and potential risks in the workplace. The internet is built on an engineering concept that is both robust and fragile, meaning users have access to websites around the world, but that access is subject to failure at any connection. Digital transformation extends and expands these new points of fragility, obscuring risk in a cyber void. In the physical world, humans are more aware of risk exposures. In a digital environment, risks are hidden beneath complexity.

Technology has driven productivity gains and prosperity in emerging and developed economies, adding convenience to many parts of our lives; however, cyber risks expose inherent vulnerabilities in cobbled-together systems. Email, social media, third-party partners, mobile devices and now even money move at speeds that increase the possibility for error and reduce our ability to “see” risk exposures that manifest within and beyond our perceptions of risk.

Developers and users of technology must begin to understand how the design and implementation of digital transformation create risk exposures. A “rush to market” mindset has put security on the back burner, leaving users on their own to figure it out instead of making security a market differentiator. Technology developers must begin to collaborate on how security can be made more intuitive for users and tech support. Tech SROs (self-regulatory organizations) are needed to stay ahead of bad actors and government regulation. Users must also understand the limits of technology to solve challenges by building in accommodations for how people work together, share and complete specific tasks.

Instead of adopting simple issues like the insider threat that pale in comparison to the larger issue of the human element, we miss the forest for the blades of grass. The first two principles are designed to support improvements in the human element, but a new risk practice must be developed with the end goals of simplicity, security and efficient operations as products of risk governance.

I will address cognitive hacks separately;[23] these are some of the most sophisticated threats in risk governance and require special treatment.

The human element principle is a focus on designing solutions that address cognitive load, build situational awareness and manage risks at the intersection of the human-to-human and human-to-machine interaction.[24],[25],[26] Apple, Amazon, Twitter and others have learned that simplicity works to promote human creativity for growth. Information security and risk governance must become intuitive and seamless to empower the human element.

This topic will be revisited in intentional design, the second pillar, but for now, let’s suffice it to say that a focus on the human element will create a multiplier effect in terms of productivity, growth, new products and services that do not exist today. Each of the five principles are a call to action to think more broadly about risks today and the future.

For now, let’s move on to principle #4, intelligence and modeling.

Principle #4: Intelligence & Modeling

“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

– George Box, Statistician

Box’s warning referred to the inclination to present excessively elaborate models as more correct than simple models. In fact, the opposite is true: Simple approximations of reality may be more useful (e.g., E=MC2). More importantly, Box further warned modelers to understand what is wrong in the model. “It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad (Box 1978).” Expanding on Box’s sentiment, I would add that useful models are not static and may become less useful during a change in circumstances or as new information is presented.

For example, risk matrices have become widely adopted in risk practice and, more recently, in cybersecurity. A risk matrix is a simple tool to rank risks when users do not have the skill or time to perform more in-depth statistical analysis.[27] Unfortunately, risk matrices have been misused by GRC consultants and risk practitioners, creating a false sense of assurance among senior executives. Good risk governance demands more rigor than simple risk matrices.

First, I want to be clear that the business intelligence and data modeling principle is not proposed as a big data project. Big data projects have gotten a bad rap, with conflicting examples of hype about the benefits, as well as humbling outcomes as measured in project success.[28] Principle #4 is about developing structured data governance in order to improve business intelligence for better performance.

Let me give you a simple example: In 2007, prior to the start of the Great Recession, mutual funds had used limited amounts of derivatives to manage risk and boast returns. Wall Street began to increase leverage using derivatives to gain advantage; however, firms relied on manual processes and were unable to easily quantify increased exposure to counterparty risk.[29] A simple question like “what is my total exposure?” took weeks – if not months – to gather and did not include comprehensive answers about impacts to fund performance if specific risk scenarios occurred. We know what happened in 2008, and many of those risks materialized without the risk mitigation needed to offset downside exposure.[30]

Without getting too wonky, manual operational processes for managing collateral and heavy use of spreadsheets and paper contracts slowed the response rate to answer these questions and minimize risk in a more timely manner. Organizations need to understand the strategic questions that matter and create the ability to answer them in minutes, not months. Good risk governance proactively defines strategic questions and refines them as information changes the firm’s risk profile.

Business intelligence and data modeling is an iterative process of experimentation to ask important strategic questions and learn what really matters. I separated the two skill sets because the disciplines are different and the capabilities are specific to each organization.[31],[32] The key point of the intelligence and modeling principle is to incorporate a commitment in risk governance to business intelligence and data modeling, along with the patience to develop the skills needed to support business strategy.

Principle #4 should be designed to better understand business performance, reduce inefficiencies, evaluate security and manage the risks critical to strategy. This is a good place to transition to principle #5, capital structure.

Principle #5: Capital Structure

A firm’s capital structure is one of the key building blocks for long-term success for any viable business, but too often, even well-established organizations stumble (and many fail) for reasons that seem inexplicable.[33] The CFO is often elevated to assume the role of risk manager, and in many firms, staff responsible for risk management report to a CFO; however, upon further analysis, the tools used by CFOs may be too narrow to manage the myriad risks that lead to business failure.

Finance students are well-versed in weighted average cost of capital calculations to achieve the right debt-to-equity mix. Organizations have become adept at managing cash flows, sales, strategy and production during stable market conditions. But how do we explain why so many firms appear to be caught flat-footed during rapid economic change and market disruption? Why is Amazon frequently blamed for causing a “retail apocalypse” in several industries? The true cause may be a pattern of inattentional blindness.[34]

Inattentional blindness is when an individual [or organization] fails to perceive an unexpected stimulus in plain sight. When it becomes impossible to attend to all the stimuli in a given situation, a temporary “blindness” effect can occur, as individuals fail to see unexpected (but often salient) objects or stimuli. In a Harvard Business Review article, “When Good Companies Go Bad,” Donald Sull, Senior Lecturer at the MIT Sloan School, and author Kathleen M. Eisenhardt explain that active inertia is an organization’s tendency to follow established patterns of behavior—even in response to dramatic environmental shifts.

Success reinforces patterns of behavior that become intractable until disruption in the market. According to Sull,

“Organizations get stuck in the modes of thinking that brought success in the past. As market leaders, management simply accelerates all their tried-and-true activities. In trying to dig themselves out of a hole, they just deepen it.”

This may explain why firms spiral into failure, but it doesn’t explain why organizations miss the emergence of competitors or a change in the market in the first place.

Inattentional blindness occurs when firms ignore or fail to develop formal processes that proactively monitor market dynamics for threats to their leadership. Sull and Eisenhardt’s analysis is partially correct in that when firms react, the response is typically half-baked, resulting in damage to capital – or worse, a race to the bottom.

Interestingly, Sull also suggests that an organization’s inability to change extends to legacy relationships with customers, vendors, employees, suppliers and others, creating “shackles” that reinforce the inability to change. Contractual agreements memorialize these relationships and financial obligations, but are rarely revisited after the deals have been completed. Contracts are risk-transfer tools, but indemnification language may be subject to different state laws. How many firms truly understand the risk exposure and financial obligations in legacy contractual agreements? How many firms understand the root cause of financial leakage in contractual language?[35]

Insurance companies are scrambling to mitigate cyber insurance accumulation risks embedded in legacy indemnification agreements.[36],[37] These hidden risks manifest because organizations lack formal processes to adequately assess legacy obligations, creating inattentional blindness to novel risks. Digital transformation will only accelerate accumulation risks in digital assets.

To summarize, the tools to manage capital do not stop with managing the cost of capital, cash flows and financial obligations. Capital can be put at risk by unanticipated blind spots in which risks and uncertainty are viewed too narrowly.

The first pillar, cognitive governance, is the driver of the next four pillars. The five pillars of a cognitive risk framework represent a new maturity level in enterprise risk management, which I propose to broaden the view of risk governance and build resilience to evolving threats. It is anticipated that more advanced cognitive risk frameworks will be developed by others (including myself) over time.

The treatment of the remaining four pillars will be shorter and focused on mitigating the issues and risks described in cognitive governance. Intentional design is the next pillar to be introduced.

[1] https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf

[2] https://www.digitalistmag.com/technologies/analytics/2015/09/28/understanding-three-lines-of-defense-part-2-03479576

[3] http://riskoversightsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Risk-Oversight-Solutions-for-comment-Three-Lines-of-Defense-vs-Five-Lines-of-Assurance-Draft-Nov-2015.pdf

[4] https://www.thoughtco.com/the-maginot-line-3861426

[5] http://hrmars.com/admin/pics/1847.pdf

[6] https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/22394/slovic_241.pdf?sequence=1

[7] https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ef56/87859fc1b5d8c85997e4c142ad8a1c345451.pdf

[8] https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/everyday-matters-tone-top-important

[9] https://ponemonsullivanreport.com/2016/05/third-party-risks-and-why-tone-at-the-top-matters-so-much/

[10] https://ethicalboardroom.com/tone-at-the-top/

[11] http://www.thepumphandle.org/2013/01/16/how-do-we-perceive-risk-paul-slovics-landmark-analysis-2/#.XTdZY5NKg1g

[12] https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/chances-are-youre-not-as-open-minded-as-you-think/2019/07/20/0319d308-aa4f-11e9-9214-246e594de5d5_story.html?utm_term=.a7d3b39a4da3

[13] https://hbr.org/2017/11/the-key-to-better-cybersecurity-keep-employee-rules-simple

[14] https://www.massivealliance.com/blog/2017/06/13/public-sector-organizations-more-prone-to-cyber-attacks/

[15] https://securitysifu.com/2019/06/26/cybersecurity-staff-burnout-risks-leaving-organisations-vulnerable-to-cyberattacks/

[16] https://dynamicsignal.com/2017/04/21/employee-productivity-statistics-every-stat-need-know/

[17] https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/2037.pdf

[18] https://www.cii.co.uk/media/6006469/simon_ashby_presentation.pdf

[19] https://www.skybrary.aero/index.php/The_Human_Factors_%22Dirty_Dozen%22

[20] https://riskandinsurance.com/the-human-element-in-banking-cyber-risk/

[21] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/insider-threat-the-human-element-of-cyberrisk

[22] https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-how-to-good-cyber-hygiene.html

[23] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2955727_Cognitive_hacking_A_battle_for_the_mind

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_load

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Situation_awareness

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human%E2%80%93computer_interaction

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_matrix

[28] https://www.techrepublic.com/article/85-of-big-data-projects-fail-but-your-developers-can-help-yours-succeed/

[29] https://www.thebalance.com/reserve-primary-fund-3305671

[30] https://www.history.com/topics/21st-century/recession

[31] https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2016/01/07/big-data-uncovered-what-does-a-data-scientist-really-do/#3f10aa82a5bb

[32] https://www.datasciencecentral.com/profiles/blogs/updated-difference-between-business-intelligence-and-data-science

[33] https://hbr.org/1999/07/why-good-companies-go-bad

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inattentional_blindness

[35] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/leakage.asp

[36] https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/research/centres/risk/downloads/crs-rms-managing-cyber-insurance-accumulation-risk.pdf

[37] https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2018/08/20/498584.htm

James Bone’s career has spanned 29 years of management, financial services and regulatory compliance risk experience with Frito-Lay, Inc., Abbot Labs, Merrill Lynch, and Fidelity Investments. James founded Global Compliance Associates, LLC and TheGRCBlueBook in 2009 to consult with global professional services firms, private equity investors, and risk and compliance professionals seeking insights in governance, risk and compliance (“GRC”) leading practices and best in class vendors.

James is a frequent speaker at industry conferences and contributing writer for Compliance Week and Corporate Compliance Insights and serves as faculty presenter and independent consultant for several global consulting firms specializing in governance, risk and compliance, IT compliance and the GRC vendor market. James created TheGRCBlueBook.com to provide risk and compliance professionals with transparency into the GRC vendor marketplace by creating a forum for writing reviews on GRC products and sharing success stories on the risk practices that are most effective.

James is currently attending Harvard Extension School for a Master of Arts in Management with an emphasis in accounting and finance. James received an honorary PhD in Letters from Drury University in Springfield, Missouri and is a member of the Breech Business School Hall of Fame as well as the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. Having graduated from the Boston University Graduate School of Education, James received his M.Ed. in Management and Organizational Design in 1997 and a Bachelor of Arts in Business Administration from Drury University in 1980.

James Bone’s career has spanned 29 years of management, financial services and regulatory compliance risk experience with Frito-Lay, Inc., Abbot Labs, Merrill Lynch, and Fidelity Investments. James founded Global Compliance Associates, LLC and TheGRCBlueBook in 2009 to consult with global professional services firms, private equity investors, and risk and compliance professionals seeking insights in governance, risk and compliance (“GRC”) leading practices and best in class vendors.

James is a frequent speaker at industry conferences and contributing writer for Compliance Week and Corporate Compliance Insights and serves as faculty presenter and independent consultant for several global consulting firms specializing in governance, risk and compliance, IT compliance and the GRC vendor market. James created TheGRCBlueBook.com to provide risk and compliance professionals with transparency into the GRC vendor marketplace by creating a forum for writing reviews on GRC products and sharing success stories on the risk practices that are most effective.

James is currently attending Harvard Extension School for a Master of Arts in Management with an emphasis in accounting and finance. James received an honorary PhD in Letters from Drury University in Springfield, Missouri and is a member of the Breech Business School Hall of Fame as well as the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. Having graduated from the Boston University Graduate School of Education, James received his M.Ed. in Management and Organizational Design in 1997 and a Bachelor of Arts in Business Administration from Drury University in 1980.