Identifying, prioritizing and evaluating risks are crucial to any business’s long-term success. MetricStream’s Yo McDonald lays out how specific biases affect these processes and ways to find them.

We are all familiar with the risk/reward terminology. Risk is everywhere, and identifying risks is an art of applying scientific principles of known and unknowns. The knowns are a phenomenon of the past, and unknowns are the transformation of the presence in the future. The biases in risk identification evolve from individual, institutional or global experiences. The biases that effect risk identifications leading into the risk prioritizations process include the following:

Cognitive Bias – A collection of predispositions and perceptions – often influenced by incentives, wants and fears – that could affect the risk assessment process.

Confirmation Bias – As humans, we are always seeking approval from others who will confirm our position. During risk identification, this may lead to a failure to capture a range of alternative risks in an organization.

Groupthink Bias – Conducting a risk identification in a group setting might lead to thoughts of a population who think alike. In the process, an important risk raised by an outlier may be ignored due to a false consensus effect.

Availability Bias – Our minds remain focused on things we see and hear frequently. For example, if there are a series of cyberattacks in the news, even if its likelihood of occurrence is lower in your organization, it may end up as a top risk.

Hindsight Bias – When decisions are made based only on what went wrong, it could result in identifying risks and processes that may not be applicable in the future.

In order to establish an effective risk identification process, identification of all existing biases is key. Primary ways to identify such biases include:

Open Communication

Having open communication, listening and asking for the facts are all important steps – along with listing what may or may not be considered risks by digging deeper into your organization.

Conducting Risk Surveys, Interviews and Workshops

By sending broad surveys, various perspectives can be gathered. After reviewing the responses, one-on-one interviews can be conducted with key stakeholders to gain greater insights. Lastly, the findings from surveys and interviews can be presented to the C-suite and risk committee for final decision-making.

Once biases are successfully removed, risk prioritization and principles of risk evaluation involve the following methods:

Qualitative Risk Evaluation

Most risk managers apply qualitative methods to evaluate risks. This leads to subjectivity. One simple method to reduce subjectivity for smaller projects is to apply the “impact likelihood” scale. This involves measuring impact and likelihood in a scale of:

- Very Low

- Low

- Medium

- High

- Very High

Each impact and likelihood can be assigned a number from 1 to 5 for Very Low to Very High respectively. See table below:

| Type | Scale | Percent |

| Very Low | 1 | 1 – 20% |

| Low | 2 | 21 – 40% |

| Medium | 3 | 41 – 60% |

| High | 4 | 61 – 80% |

| Very High | 5 | 81% – 100% |

Final risk rating as a product of impact and likelihood will fall in between a range of 1 and 25. The product can be translated into a subjective rating as per the below table:

| Rating | Range |

| Very Low | 1 – 5 |

| Low | 6 – 10 |

| Medium | 11 – 15 |

| High | 16 – 20 |

| Very High | 21 – 25 |

A simple example can illustrate the qualitative method.

There have been four Category 5 hurricanes (with a wind speed of 157 miles per hour or more) hitting the U.S. in the last 100 years. This means there is a 4 percent chance of a Category 5 storm hitting the U.S. in a year. Applying the qualitative principles, the likelihood of the risk is Very Low. However, the impact of a Category 5 hurricane can be devastating (i.e., Very High). The below table determines the risk rating:

| Risk | Impact | Likelihood | Risk Rating = Impact x Likelihood |

| Category 5 Hurricane in United States | Very Low: 1 | Very High: 5 | Very Low: 5 |

Although we considered the likelihood based on historic data, we need to consider external factors that might increase or decrease the likelihood over time.

If we dig deeper into the hurricane example, eight out of 35 Category 5 hurricanes were initiated in the North Atlantic Ocean in the last decade (i.e., 25 percent of Category 5 hurricanes in the past 10 years), which is a significant number to ignore. In 2020, it is forecasted that there will be 18 named storms, nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes compared to a 30-year average of 13 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes. Whether it eventually happens or not, the difference is too high to disregard. Moreover, the effect of climate change will make hurricane seasons worse over the years. As we ask more questions and are presented with clearer facts, our likelihood scale is bound to change, resulting in a shift in risk rating.

Quantitative Risk Evaluation

The quantitative risk evaluation method is objective. It uses verifiable data to determine multiple risk factors and requires a heavy volume of data, specialized software and vigorous risk models.

A simple example can illustrate quantitative evaluation: California is severely affected by wildfires every year. In order to perform quantitative fire risk evaluation, we need to characterize and combine fire behavior probabilities and effects. These probabilities are different from likelihoods based on historic data, since they depend on spatial and temporal factors controlling fire growth. The likelihood of a wildfire in a specific location is dependent on various factors, such as weather condition, topography, forest dryness and fire direction. The fire behavior distribution requires scientific computation of these factors. The impact or effect of wildfires needs to be appraised based on a common scale of infrastructure and human values susceptible to fire. Ultimately, this will determine the investment needed to evaluate the likelihood of wildfire in that location and to minimize the damage.

It might sound like the quantitative approach is the more reliable of the two. However, both methods hold equal merits. Qualitative risk should always be performed. It is the most perfect way to analyze and prioritize risks that can be broadly adopted across an organization. On the other hand, quantitative risk evaluation is vital, especially in high-risk industries, such as mining, oil and gas, construction and anything that presents a threat to the safety of workers on a day-to-day basis. Indeed, it’s a legal requirement.

The following table provides the difference between the qualitative and quantitative risk evaluation methods:

| Qualitative | Quantitative |

| Easily Performed | Objective |

| Subjective | Detailed and complex |

| Quick | Takes more time |

| Needed for smaller projects | Needed for industries with threat to safety |

| Should always be performed | Can be optional |

| Degree of overall risk is undermined | Degree of overall risk is determined |

The above methods of identifying biases and evaluating risks for strategic prioritization may result in reducing the impact of unforeseeable events, but they can never eliminate the possibilities of a failed risk prioritization, as we have experienced in 2020.

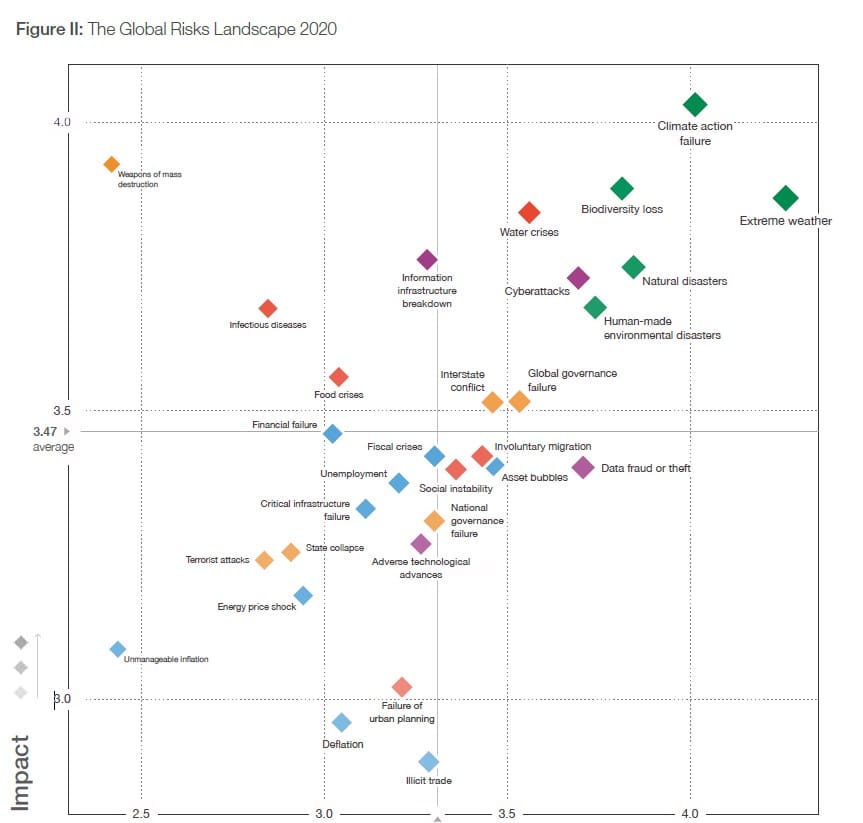

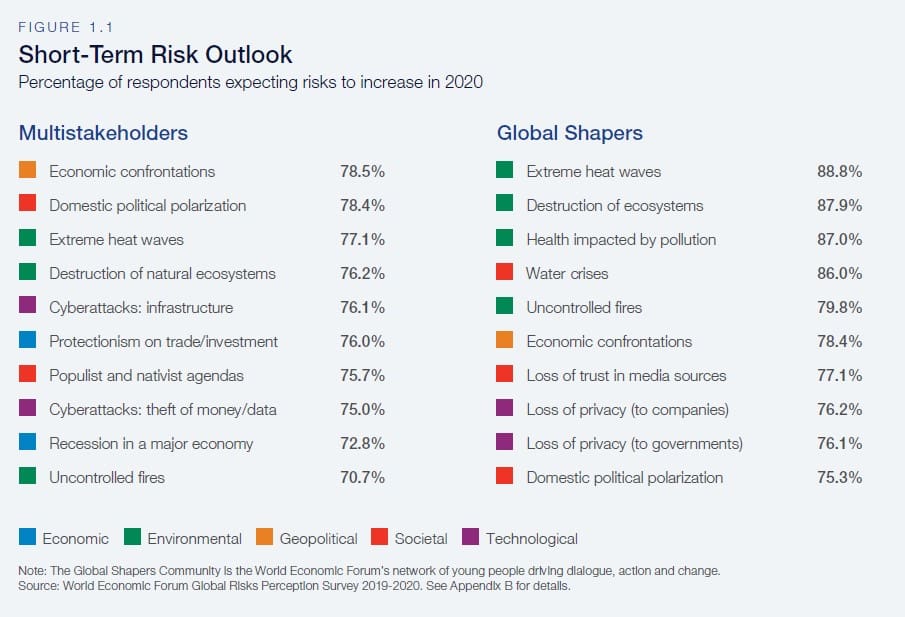

The Global Risks Report of 2020 by the World Economic Forum (WEF) prioritized climate change and related environmental issues as the top five risks in terms of likelihood. However, we have all experienced how the global pandemic has turned our worlds upside down.

Going back to the report, if one prioritizes risk based on the Global Risk Landscape 2020 (fig II), infectious disease would unlikely make it onto the prioritization list. In the short-term risk outlook (fig 1.1), the pandemic doesn’t even appear anywhere.

Once the pandemic is over, we will run into various biases while identifying future risks; therefore, all the methods to mitigate such biases will be critical. It won’t eradicate similar occurrences but will reduce the impact of these risk factors through better mitigation strategies.

In 2015, in a now famous TED Talk, Bill Gates repeatedly warned how we were not prepared for the next epidemic. During the Obama administration, when we experienced the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) and 2014 Ebola outbreaks, the former president emphasized building a public health infrastructure globally to combat the next pandemic. Unfortunately, the world was not prepared for the current COVID pandemic, and we now face the irreversible consequences of poor planning and poor risk prioritization. Let’s learn from the struggles following 9/11 and create a unified effort to prepare for the next pandemic.

Yo McDonald is Vice President of Customer Success and Engagement at

Yo McDonald is Vice President of Customer Success and Engagement at