With AI-first and AI-now calls continuing to grow throughout all types of organizations, the risk of ethical, legal and reputational damage is undeniable, but so, too, may be the benefits of using this rapidly advancing technology. To help answer the question of how much AI is too much, Ask an Ethicist columnist Vera Cherepanova invites guest ethicist/technologist Garrett Pendergraft of Pepperdine University.

Our CEO is pushing us to integrate AI across every function, immediately. I support the goal, but I’m concerned that rushing implementation without clear oversight could create ethical, legal or reputational risks. I’m not against using AI, but I’d like to make the case for a more deliberate rollout, one that aligns innovation with accountability. How can I do that effectively without appearing resistant to change? — Brandon

This month, I’m joined by guest ethicist Garrett Pendergraft to reflect on a familiar tension in today’s corporate world: the push to adopt AI immediately, and the more subtle and less comfortable question of whether the organization is actually ready for it. In other words, is asking for prudence the same as resisting innovation? And how can leaders advocate for governance without being cast as obstacles to progress?

Garrett is a professor of philosophy at Pepperdine University and has a unique perspective as someone who bridges two worlds — technology and moral philosophy — in his background. His is the ideal lens for this particular question.

***

Use the tools, not too much, stay in charge

As Vera mentioned, many years ago I studied computer science. It’s been a while since I’ve been in that world, but I’ve enjoyed staying abreast of it. And Pepperdine used to have a joint degree in computer science and philosophy, which was great to be a part of.

Most of what I’m going to share has been formulated more at the individual level for my business ethics students and some other courses I’ve done, but I think the principles apply in more general contexts, including corporate settings and executive and governance contexts.

There’s often resistance to adoption of AI tools and technology in general. In the humanities, for example, there’s a lot of resistance to these sorts of things. And, of course, with AI tools and LLMs and the way that students are using them, that feeds the resistance.

A slogan I came up with was inspired by Michael Pollan’s food rules from about 15 years ago, something like, “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” That structure seemed to fit well with my thoughts on using AI: “Use the tools, not too much, stay in charge.”

With the first part, “use the tools,” I think the key is to use them well. And when it comes to higher education, the temptation is to pretend that they don’t exist or try to set up a cloister where they’re not allowed.

For academics, using the tools well involves embracing the possibilities and taking the time to figure out how what we do can be enhanced by what these tools have to offer. So, I think that general principle applies across the board. And I think the temptation in other fields, and in the tech field in particular, is to rush headlong and try to use everything.

This applies maybe more to the “not too much” point, but every week there’s another news story about someone who has been reckless with AI tools. A recent one was Deloitte Australia, which created a report for the government, being paid somewhere around $400,000 for it, and had to admit the report contained a lot of fabricated citations and other clearly AI-generated material. And so that was embarrassing and they had to refund the government and redo the report.

The key when it comes to things like human judgment is to view even agentic tools as like having an army of interns at your disposal. You wouldn’t just have your interns do the work for you and then send it off without checking it first.

But this very thing is happening, whether in the Deloitte Australia example, or in cases of briefs filed in various court jurisdictions that include hallucinated citations and other fabrications, or the summer reading list published by a newspaper, complete with fake books, that turns out to have been AI generated.

Sometimes friction is the point

The first point on the moral side of things is just not forgetting about your responsibilities to deliver the work that you signed up to do. I think on the practical side, it’s tempting to assume that if we start using these tools, they will just make the quality better or make us faster at producing that quality.

But according to one recent study, advanced engineers who used these tools took even longer to do the task than without them. While time savings may be possible, whatever the industry, the first step is to figure out your baseline quality and a baseline amount of time you expect a task to take. And then you systematically evaluate what these tools are doing for you, whether they actually are improving quality or making you faster.

If they don’t improve quality or save time, you must resist the temptation to use them, even though they’re admittedly fun to use. And that’s where I think the “not too much” part of my advice is useful. Human judgment is crucial because human judgment means figuring out which elements of your work life, social life and family life need to have that human nuance and which of them can be outsourced.

Sometimes refraining from AI use is necessary because you need to just give the work a human touch. And other times refraining is necessary because there’s a certain amount of friction that actually produces learning and growth.

Something we’re always trying to preach to our students, borrowed from the Marine Corps., is: “Embrace the suck.” I think this is useful advice because all of us are partly where we are today because we went through some friction and some struggle and we embraced it to one extent or another.

Again, this is where human judgment is necessary. It’s important to recognize what kinds of friction are essential to growth in skill and in capacity and what kinds of friction are holding us back and therefore can be dispensed with.

There are things that AI allows you to do that you couldn’t do before, which means that your agency has been extended or enhanced, but your human judgment is necessary to make the determination of whether your agency is being enhanced to diminished.

It’s better to use AI well than to ignore it, but I would argue that not using it at all is better than using it poorly.

Remember what you’re trying to do in the first place

Going back to Brandon’s question, I think resistance to the use of automation and AI often comes from a fear that we won’t be able to stay in charge, and I think one of the defining characteristics of the rush to automation is failing to stay in charge. (This is how we end up with fabricated reading lists and hallucinated citations.) We can avoid the knee-jerk resistance and also the reckless rush by thinking about how to stay in charge.

Examples of the rush to automation include companies like Coinbase or IgniteTech, which required engineers to adopt AI tools and threatened to fire them if they didn’t do it quickly enough.

I think the issue here is just the same issue from that classic management consulting article from the 1970s, “On the Folly of Rewarding A While Hoping for B.”

The article gives examples of this in politics, business, war and education. And I think the rush to automation is another example of this. If you want your workers to be more productive, and you’re convinced that they can benefit from leveraging AI tools, then you should just ask for more or better output. If you simply require use of AI tools — focusing on the means rather than the desired end result — then people won’t necessarily be using the tools for the right reasons.

And if people aren’t using AI tools for the right reasons, they might end up producing the opposite effect and being less productive. It’s like the cobra effect, during British colonial rule of India, where they tried to solve the problem of too many cobras by offering a bounty on dead cobras. So people just bred cobras and killed them and turned them in for the bounty, with the end result of more cobras overall.

A rush to automation, especially if it includes a simplistic requirement to use AI tools, can do more harm than good.

We should focus on what we’re actually trying to do out there in the world or in our industry and try to figure out exactly how the tools can help with that. I think the bottom line is that the key element that is always going to be valuable, the irreplaceable part is always going to be human judgment. These tools will become more powerful, more agentic, more capable of working together and making decisions. The more complex it gets, the more we’re going to have to be aware of decision points, inputs and outputs and how human judgment can ensure we don’t end up in the apocalypse scenarios or even just the costly or embarrassing scenarios for our business.

Instead, we want to make the most of these new capacities for the good of our business and the overall good of everyone.

***

Garrett’s perspective is so rich and so powerful. And we’ve certainly seen the “Rewarding A While Hoping for B” movie before. Remember Wells Fargo’s attempt to monitor remote employee productivity by tracking keystrokes and screen time? Measure keystrokes, get lots of keystrokes, as the saying goes.

The lesson applies directly to AI. Thoughtless adoption can create more risk, not less. Human judgment remains an irreplaceable asset. So, Brandon, when you speak with your CEO, don’t frame your concern as “slow down.” Frame it as:

- Let’s aim for better outcomes, not just more AI.

- Let’s pilot, measure and learn, not blindly deploy.

- And let’s keep humans in charge of the decisions that matter.

Use the tools, not too much, stay in charge. That’s not resistance to change. It’s how you make sure AI becomes a force multiplier for your company instead of an expensive shortcut to artificial stupidity.

Yes, You Can Fire an Employee for a Problematic Post, but Should You?

Almost anything can be viewed as politically incendiary, increasing the temptation for quick action

Read moreDetailsReaders respond

Last month’s question came from a director serving on the board of a listed company. An employee’s personal post about a polarizing political event went viral, dragging the company into the headlines. Terminating the employee looked like the easy answer, but the dilemma raised deeper questions: When free speech, company reputation and political pressure collide, where does the board’s fiduciary duty lie?

In my response, I noted: “The phrase ‘This is what we stand for’ gets repeated a lot in moments like this. Yet in situations like this, few companies pause to ask whether they actually do stand for the things they say they do. Do your values genuinely inform your decisions, or do they surface only when convenient? When termination is driven more by external pressure than internal principle, it’s not good governance for the sake of the company’s long-term health. It’s managing the headlines.

“Consistency matters, and so does proportionality and due process: facts verified, context understood. Boards’ ability to demonstrate that they provided informed oversight and decision-making is tied up in the integrity of the process. The reputational damage from inconsistency and hypocrisy can be far greater than from a single employee’s poorly worded post.

“Another complication is that almost anything can be viewed as politically incendiary today, which was not the case in the past. The temptation for quick action to ‘get ahead of the story’ is sometimes political opportunism in disguise. Boards under public scrutiny may convince themselves they’re defending values, when they’re really just hedging against personal liability.” Read the full question and answer here.

“He who rises in anger, suffers losses” — YA

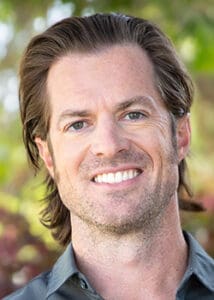

Vera Cherepanova

Vera Cherepanova