While they did identify examples of shocking activity, Buzzfeed’s and ICIJ’s FinCEN Files didn’t necessarily expose widespread wrongdoing, as its authors claimed. Instead, the story revealed glaring inefficiencies in anti-money laundering efforts.

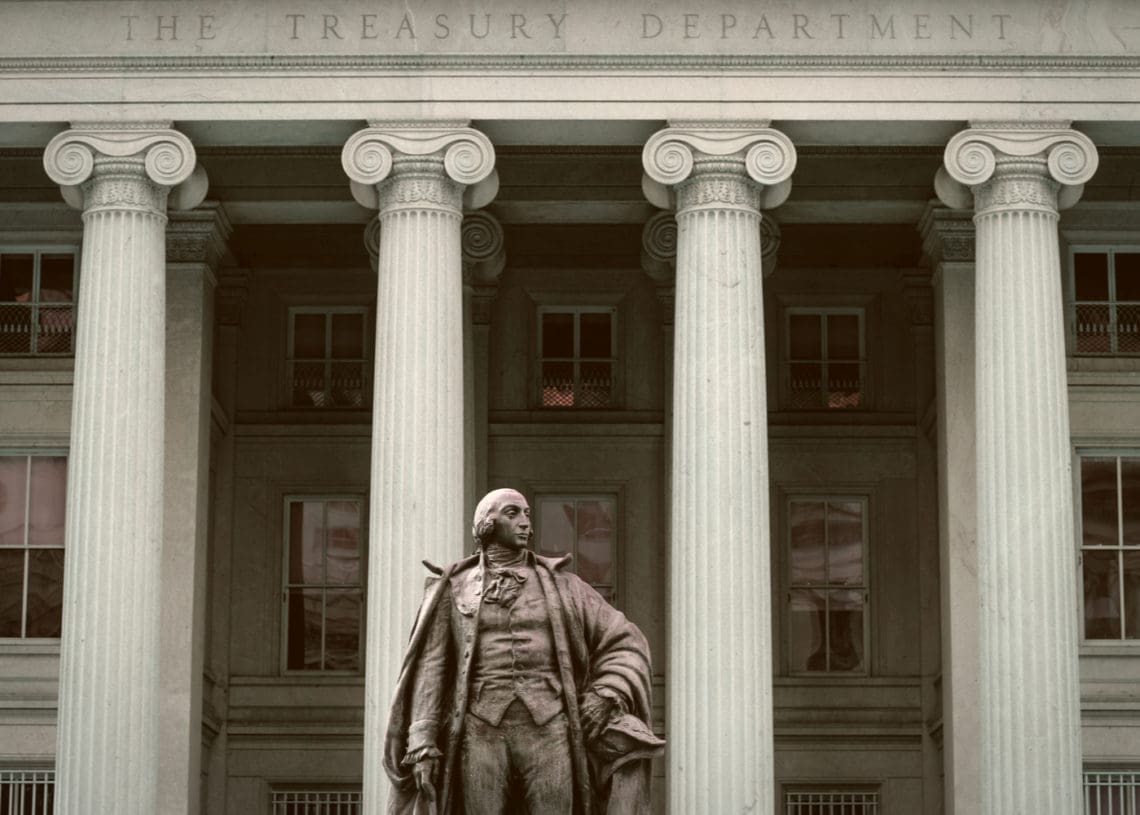

In September 2020, BuzzFeed and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) published information on over 2,100 leaked documents from the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Known as the FinCEN Files, these documents revealed the high levels of suspicious activity reports (SARs) filed by banks, which many saw as an indication of widespread money laundering.

By law, banks are required to file SARs, but it’s important that these reports are not mistaken for proof that a crime has taken place. The fact is that the proportion of SARs resulting from genuine nefarious activity, as opposed to a bank simply filing any potentially suspicious transaction to meet its regulatory obligations, is not known.

Indeed, the banks involved in the leak may have been acting with the best intentions, with many filing defensive SARs as soon as the internal control frameworks identified any suspicious activities, ensuring they didn’t fall foul of their regulatory requirements. Conflictingly, however, leaked data analyzed by Kroll suggests that a number of banks reporting the largest volumes of suspicious transactions, or with the largest values, were subsequently fined by the regulators for anti-money laundering (AML) violations in the past.

The leaks actually give us little new information about money laundering; instead, they highlighted the fact that current AML systems are not functioning as optimally as they should. The FinCEN leaks may have shown that banks are filing SARs regularly, but based on the number of fines and money-laundering scandals, they also revealed that a system of defensive SAR filing does not produce optimal outcomes that successfully reduce financial crime.

Rather than trying to limit all exposure to every possible money-laundering risk, banks should be finding better ways to mitigate these risks to operate safely in high-risk environments. This will require a firm commitment from the banks to develop stronger controls and infrastructure. Rather than simply turning down business, banks will need a much more active engagement with AML procedures: buy-in from each tier of management, ongoing monitoring of AML risk and a likely increase in spending on resources.

Risk Mitigation

The FinCEN leaks confirmed there is a clear profile for a “risky” transaction, but this doesn’t mean that banks should limit their activities or make absolute prohibitions according to these transaction characteristics.

Refusing to deal with transactions in certain markets is simply not a realistic solution. Indeed, it is clearly beneficial for the sector as a whole that high-risk business is directed through regulated institutions so that suspicious activity can be brought to the attention of the regulators, instead of the transactions taking place through criminal channels.

Part of the solution to this lies in developing strong controls and infrastructure, which requires active engagement with AML procedures, a sound understanding of what constitutes a suspicious transaction, reliable data and the ability to respond to the identification of a suspicious transaction quickly. This process starts with obtaining and maintaining strong customer information using solid know your customer (KYC) and know your business (KYB) procedures. For this reason, it is vital that banks have robust data collection, monitoring and response systems in place.

For example, SARs should not be filed just because a customer has made an unusual payment, as this alone may not be indicative of suspicious activity. It is only when a payment does not make any logical sense in the context of the customer’s profile, occupation, income and typical behavioral patterns that action needs to be taken to establish why the transaction took place, where the funds may have come from and where they are going.

As such, the overriding message to take from last year’s leaks is that filing SARs should not be seen as an onerous obligation, but instead as an opportunity to alert relevant authorities to suspicious activity and to provide useful information to help the authorities in their investigations.

An effective SAR should set out the reasons for suspicion, outline the suspected wrongdoing and be investigated in a time frame that is reasonable to comply with obligations. It is equally important to ensure high-quality information is provided within the SAR, with all the relevant details, to the authorities so that a new, stronger and more collaborative working system can be built.

Overcoming Key Challenges

In order to achieve this goal, banks need to begin by looking at their current systems. Kroll’s (Duff & Phelps rebranded to Kroll in 2021) 2020 Global Enforcement Review revealed some of the most common errors among banks that have received AML fines. The failures, identified by regulators, represent several common operating weaknesses that prevent successful reporting of suspicious transactions.

Common problems included inefficient transaction monitoring arrangements, inadequate resource allocation, issues with customer data and problems integrating technology and working solutions. As a result, sufficient information is not collected on customer behaviors in many cases, and investigations into unusual transactions or actions may not come under adequate scrutiny.

Resource allocation may present another obstacle to the monitoring and reporting of suspicious transactions since inadequate financial or personnel resources may lead to delays in reporting or result in ineffective investigations. Over-resourcing, however, without the appropriate understanding of transactional risks, can also impact a bank’s ability to respond to suspicious activities. This also becomes an issue when the knowledge brought in by experienced contractors and external advisors is not retained, leading to the same mistakes and failures in the investigation process.

These challenges can often be resolved through the implementation of transaction monitoring systems that use advanced analytical technologies. This is not a “quick fix” solution, though, and will still require sound knowledge of the risks relevant to a bank.

Legacy data systems may also be problematic since it can often be almost impossible to collate data into a single database after it has been subjected to different procedures and technology elsewhere. This may result in a lack of control over the data and ultimately provide poor outcomes from seemingly advanced monitoring systems. To combat this, legacy data systems should be updated or replaced.

Best Practice Models for AML

While there is certainly some work to be done by the banks, the support of regulators and enforcement agencies is also vital. The U.K. currently has the leading best practice model for how regulators, financial intelligence units (FIUs) and the private sector can collaborate successfully.

In 2015, the U.K. launched the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT), creating a transparent, safe and legally sanctioned environment wherein the public and private sector can share information on crime typologies and develop new methods of detection. Additionally, the National Economic Crime Centre (NECC) was created to promote broader cooperation between FIUs and other agencies, both within and outside of the country.

There are still shortcomings with these systems, as only the largest financial institutions in the U.K. can currently join the JMLIT, meaning the smaller banks miss out on its benefits. At the same time, data sharing and collaboration with European regulators and agencies has been impacted by the U.K.’s exit from the EU. It therefore seems likely that Brexit will hinder the U.K.’s ability to conduct cross-border investigations that affect both jurisdictions.

As a result, despite being widely recognized as the best practice model for AML efforts, there are still some issues to be resolved with the U.K. approach. For instance, it has proved largely inadequate in addressing the millions of pounds hidden in the London property market, which have been laundered out of Russia, according to a report by the Treasury and Home Office.

Ultimately, closer cooperation between all parties is required here, as the more collaborative and holistic AML measures are, the more effective their outcomes. While banks play an important part, they alone cannot, and should not, be held responsible for the prevention of money laundering. After all, no bank has control over secrecy laws, regulations or verification systems in its jurisdiction.

The primary aim of any AML framework should be to combat money laundering in the most effective manner possible. No approach will ever be perfect, but if the current way of working continues to produce suboptimal outcomes, then banks need to change their perspective on AML and reevaluate their strategies. Taking a more proactive and collaborative approach would be a strong first step in this direction.