In 1980, the Libertarian Party advocated abolishing child labor laws entirely, and two years later the Reagan Administration proposed regulatory changes before public outcry forced withdrawal. Katie Martin of Avetta connects that decade’s battles to today’s reality, where children as young as 12 work overnight shifts around toxic chemicals and fast-moving production lines and maps concrete steps companies can take to prioritize supply chain transparency beyond Tier 1 suppliers.

The 1980s have enjoyed a cultural revival in recent years. Neon colors, synth-pop soundtracks and big hair have all made their way back into the zeitgeist — thanks in no small part to the massive popularity of Netflix’s hit show “Stranger Things,” which recently aired its series finale. The show delivers a nostalgic, supernatural adventure built around a group of kids fighting monsters while juggling homework, crushes and the occasional mall job. It’s fun, escapist entertainment.

But while viewers follow the fictional teens of Hawkins, Indiana, as they clock long hours at Scoops Ahoy or Family Video, it’s worth remembering that one of the decade’s darkest realities was not science fiction at all — it was the very real battle over child labor.

And perhaps most unsettling: more than 40 years later, we are still fighting it.

Child labor in the 1980s

The 1980s are often remembered as a decade of economic optimism and deregulation. Corporate consolidation accelerated, manufacturing moved offshore and the call for “smaller government” became a defining political ideology. Within that landscape, some influential voices targeted regulations that had long been considered settled, child labor laws among them.

In 1980, Libertarian Party vice presidential nominee David Koch made headlines for advocating the abolition of child labor laws entirely. While his position didn’t gain mainstream traction, it signaled a broader push to reevaluate protections established under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Only two years later, the Reagan Administration proposed regulatory changes that would have expanded the types of jobs 14- and 15-year-olds could perform and extended their allowable work hours. The administration also floated lowering the minimum wage for students, a move critics argued would encourage employers to hire minors over adults.

Though these proposals were ultimately withdrawn after public outcry, the decade still saw significant growth in illegal child labor practices. Investigative reporting at the time documented that child labor violations doubled between the first and second halves of the 1980s. These violations included excessive hours, employment in hazardous environments and, in some cases, exploitation in unregulated workplaces.

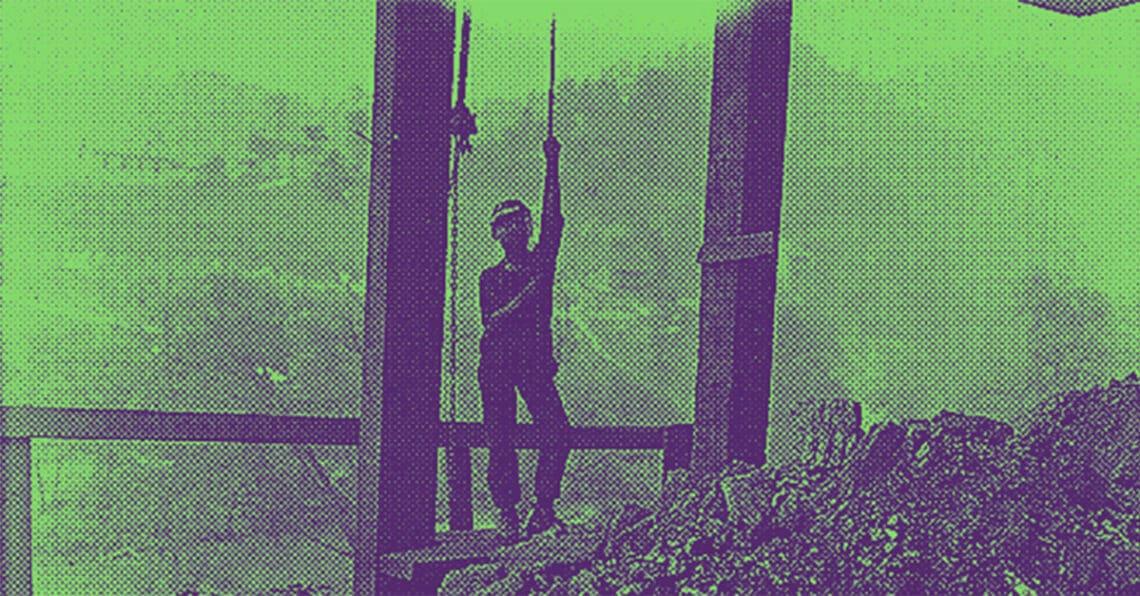

Child labor didn’t disappear—it just became harder to see

Fast forward to today, and many assume child labor in the United States is a relic of the past, something addressed by early 20th-century reforms and preserved in grainy black-and-white photographs. Unfortunately, that assumption is dangerously outdated.

The US Department of Labor has reported a steady rise in child labor violations over the past several years, with minors increasingly found working in manufacturing plants, slaughterhouses, construction sites and industrial food processing facilities. These are not “kids helping out after school.” They are children, sometimes as young as 12, working overnight shifts around heavy equipment, toxic chemicals and fast-moving production lines.

Several factors are driving this resurgence:

- Labor shortages tempt employers or contractors to hire underage workers, sometimes through staffing agencies or subcontractors.

- Supply chain complexity makes it difficult for companies to track who is performing work at every tier.

- Migration patterns, with vulnerable minors, especially unaccompanied youth, seeking work to support themselves or family members.

- Legislative efforts in some states to loosen restrictions on teen work hours or expand the hazardous occupations minors can perform.

This modern landscape mirrors the 1980s in one critical way: Policy debates and business pressures continue to create loopholes that allow child labor to re-emerge in plain sight.

Administration Heightens Enforcement Focus on Tariff Evasion & ‘Transshipment’

White House expresses zero tolerance for ‘transshipment’ schemes

Read moreDetailsThe new efforts to loosen child labor protections

In recent years, several states have introduced or passed legislation to weaken child labor protections. These proposals have included:

- Extending the number of hours minors can work on school nights.

- Allowing 14- and 15-year-olds to work in industrial environments previously deemed hazardous.

- Reducing permitting requirements that ensure age verification.

- Removing restrictions on late-night shifts or overnight work.

Proponents argue these measures provide teens with more opportunities to earn money and support local economies. But history — and contemporary data — tell another story. When protections loosen, exploitation increases. Vulnerable youth often lack the power to refuse unsafe assignments, and employers struggling to meet demand may look the other way.

We’ve already seen what this leads to: significant injuries, wage theft and unsafe working conditions that disproportionately affect minors who lack the legal and financial resources to advocate for themselves.

Global supply chains and hidden risk

While child labor violations in the US are troubling on their own, the global supply chain presents an even broader challenge.

Despite widespread corporate commitments to social responsibility, child labor remains deeply embedded in global production networks. Agriculture, textiles, mining, electronics, food production and packaging all carry documented risks. In some countries, children work in hazardous mines extracting materials for everyday electronics. In others, they perform dangerous agricultural labor or operate heavy machinery in unregulated workshops.

For companies operating internationally or purchasing from international suppliers, the risks are often hidden several tiers deep. A brand may have strong policies in place with Tier 1 suppliers, but risk increases dramatically further down the chain. Subcontracting, informal labor arrangements and high turnover exacerbate the lack of transparency.

One significant advantage of the modern era is that information is more accessible than at any other point in history, and it can be used to protect children from exploitative labor practices.

What companies can do

The resurgence of child labor is not an unsolvable problem. Companies possess the ability to monitor their suppliers, verify workforce practices and enforce compliance standards. But doing so requires intentionality, investment and a recognition that reputational risk is only one part of the equation: legal and ethical responsibilities matter even more.

Here are steps organizations can take to identify and address child labor in their supply chains:

- Prioritize supply chain transparency beyond Tier 1: Most organizations focus on their direct suppliers, but risk typically exists further down the supply chain. Companies should map their supply chains as comprehensively as possible and require subcontractors, staffing agencies and labor brokers to adhere to the same labor standards as primary vendors.

- Implement strict age verification processes: Age verification cannot rely on self-reporting or easily falsified documents. Companies should require verified identification documents, government-issued work permits (where applicable), auditable hiring records and compliance attestations from subcontractors.

- Conduct regular, unannounced audits: Announced audits have their place, but unannounced inspections often reveal the most critical insights and should include interviews with workers, document review, on-site inspections and cross-checks between reported staffing levels and actual work performed.

- Monitor high-risk flags: Certain conditions increase the likelihood of child labor, such as high reliance on staffing agencies, rapid workforce expansion, high turnover rates and operations in industries or regions with known historical violations.

- Establish clear corrective action protocols: Identifying child labor must trigger immediate action. Corrective measures may include: removing minors from hazardous roles, requiring supplier retraining, penalizing noncompliant suppliers or ending supplier relationships altogether. The priority should always be the safety and well-being of the minor involved.

- Partner with community and advocacy organizations: Local NGOs, community organizations and governmental labor departments often have deeper visibility into emerging risks. Partnerships can help companies stay proactive rather than reactive. Industry coalitions like Together for Sustainability, a group of chemical procurement leaders, allow businesses to share audit data for key suppliers. Similar partnerships across industries to promote transparency and risk management with vendors continue to emerge, so companies should continue to monitor their respective industries for such coalitions.

A responsibility that goes beyond compliance

The push to loosen child labor protections in some states — and the rise in violations globally — should serve as a clear warning. Children are uniquely vulnerable to exploitation. Their safety, education and long-term well-being cannot be compromised for the sake of lower costs or faster production.

Companies must recognize that this is not simply a compliance issue. It’s a moral and human issue. The decisions leaders make today will shape whether we move closer to a future where child labor is eliminated or continue repeating the cycle that has defined past decades.

Modern companies have the power to create enough visibility to ensure their supply chains are not built on the exploitation of minors. And prevention of such exploitation is key to building healthier societies where children can learn, grow and eventually contribute to the workforce on their own terms and at an appropriate age.

The dark side of the 1980s reminds us of what happens when protections slip. Our job today is to ensure history doesn’t repeat itself.

Katie Martin is director of sustainability and innovation at Avetta, a supply chain risk management software provider.

Katie Martin is director of sustainability and innovation at Avetta, a supply chain risk management software provider.