Companies are investing heavily in cybersecurity protection, weaving it into their business models as a core function rather than a peripheral obligation. But this leaves employees facing a relentless barrage of notifications that first spark paranoia, then numb them into desensitization until they stop paying attention altogether. Stephen Ross of consultancy S-RM examines cybersecurity fatigue and explores whether organizations can address it without weakening defenses.

Cybercrime continues to surge. The FBI recorded more than 859,000 complaints in 2024, with reported losses exceeding $16 billion — a 33% jump from the previous year.

Many organizations have responded by becoming more vigilant and investing heavily in protection, no longer treating it as just another box to check for regulators. Cybersecurity is now woven into their business models, a core function rather than a peripheral obligation.

While companies are definitely on the right track, it leaves employees facing a relentless barrage of notifications: warnings that their files may not be safe, alerts about attempted breaches, reminders to reset passwords and a steady drip of news stories about major attacks.

The result is cybersecurity fatigue, an emerging phenomenon where alerts first spark paranoia, then numb employees into desensitization until they stop paying attention altogether. A phishing notification becomes just another pop-up to dismiss. A training module becomes something to click through mindlessly. In some cases, on a personal level, apathy can even harden into nihilism: my data’s already out there, so who cares?

Is this simply the cost of doing business in the digital age, a burden organizations have to bear? Or is there a way to address cybersecurity fatigue without weakening defenses?

Promise, price and limits of advanced defenses

Security information and event management systems (SIEMs) and their more advanced successors, SOAR platforms (security orchestration, automation and response), were built to tame the flood of alerts by streamlining and automating the way organizations respond. When implemented well, they can separate signal from noise, consolidating disparate warnings into a digestible feed and even triggering routine responses, such as locking a suspicious account or quarantining a compromised device. For companies willing to make the investment, these tools can be transformative, sparing analysts — and employees further downstream — from drowning in false alarms. But the price tag keeps them out of reach for many small and mid-sized firms.

Endpoint detection and response systems (EDRs) are also growing more sophisticated. Many now incorporate machine learning to recognize suspicious behavior, and some can flag activity that would have slipped past older defenses. These advances make them invaluable day-to-day, yet most vendors are reluctant to let their systems automatically suppress potential false positives because if a flagged threat turns out to be real, the liability is immense. Agent-based AI, the next frontier, holds out the promise of doing just that: autonomously sifting signal from noise. For now, though, it remains largely theoretical.

2026 Operational Guide to Cybersecurity, AI Governance & Emerging Risks

AI has shifted from an emerging fintech area to a clear operational risk linked to cybersecurity and disclosures

Read moreDetailsPractical stopgaps

For organizations that lack the budget for advanced tooling, there are still pragmatic ways to keep fatigue in check. The first is tuning their alerts. Calibrating a system so that it distinguishes a genuine threat from background noise is not just a matter of flipping a switch; it takes experience. Many companies bring in managed service providers (MSSPs) who have seen hundreds of systems and can help set thresholds that balance sensitivity with sanity. A properly tuned system may still generate a heavy stream of alerts, but it spares teams from the most obvious false positives.

Another stopgap is outsourcing security operations center (SOC) coverage. Around-the-clock monitoring is essential, but few firms can afford to keep a full roster of analysts on duty 24 hours a day, and those that try risk burning out their own teams. Again, partnering with providers offers a practical alternative: some firms hand off the midnight shift while keeping daytime monitoring in-house, while others outsource the entire function.

Finally, organizations can reduce strain by prioritizing their “crown jewels.” Not every system or data set is equally valuable, and not every alert needs to be treated with the same urgency. By identifying the assets that matter most — financial databases, customer records, proprietary designs — companies can concentrate their limited resources where the risk is greatest. An alert on a testing server might not warrant an all-hands investigation; a similar alert on the payment system almost certainly does.

Building a culture of defense

Addressing fatigue requires a cultural shift inside organizations, one that treats security not as an obligation imposed from above but as part of the daily fabric of work.

That starts with rethinking training. Too often, security awareness programs are treated as twice-a-year compliance hurdles. Employees click through dull slide decks, absorb little and resent the time lost. To stick, training must be interactive, engaging and clearly tied to the real-world threats employees face

Organizations could start by gamifying the process. Imagine departments competing for top scores on phishing simulations, with the winners earning recognition or even a pizza lunch. They could also run “red team” exercises to stage mock attacks, showing employees how a real phishing email or malicious attachment might appear in their inbox. These tactics may sound small and even playful, but they have the power to shift security from an abstract burden into a lived, memorable experience.

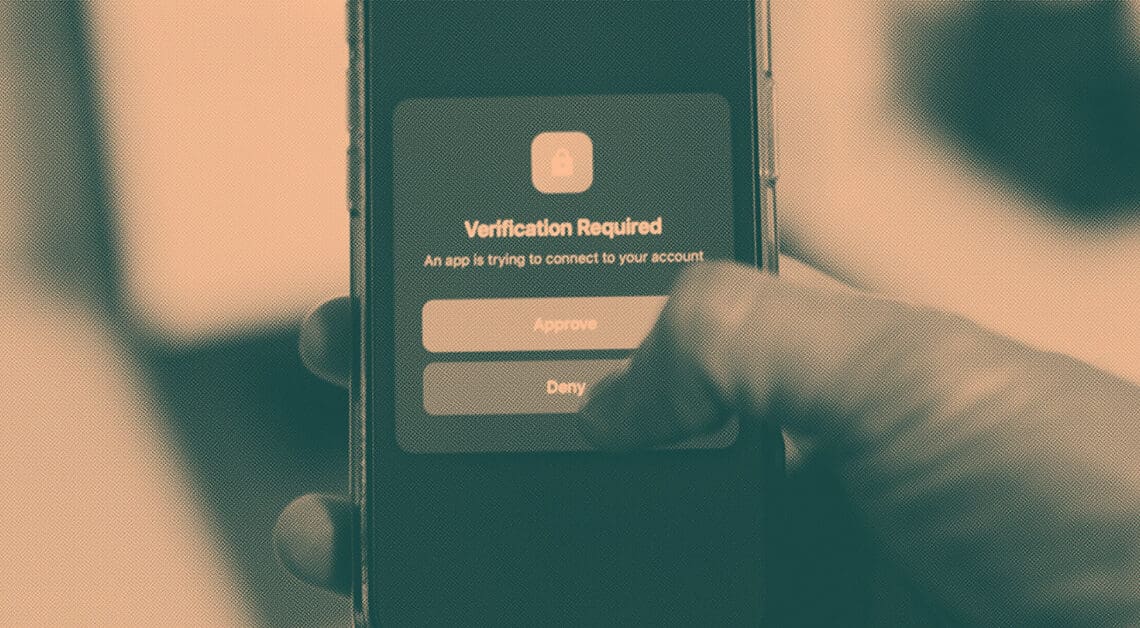

Equally important is explaining the why. Employees are far more likely to comply with requirements like multifactor authentication (MFA) or VPN use when they understand the reasoning behind them. If workers know that MFA would have stopped a real-world ransomware attack or that a VPN could have blocked an attempted intrusion on an unsecured Wi-Fi network, compliance feels less like arbitrary punishment and more like participation in collective defense. A training slide that simply says “use MFA” inspires fatigue; one that shows how MFA would have blocked a breach last month inspires cooperation.

The modern workplace can no longer be divided between “soldiers” in security and “civilians” in other roles. Every employee is part of the supply line, whether they are an engineer safeguarding code repositories, a marketing associate recognizing a phishing email, or a customer service representative securing sensitive data. Defense should be collective — but not fatiguing.

Stephen Ross is director of cybersecurity at corporate intelligence firm S-RM.

Stephen Ross is director of cybersecurity at corporate intelligence firm S-RM.