With the Senate’s decisive vote against a state AI regulation moratorium, compliance officers face a stark reality: Most organizations are using AI, but not everyone has policies governing the technology as it keeps on advancing and formal rules may depend on where you (or your customer) are located. Jennifer L. Gaskin reports on how teams are building risk-based frameworks for a world where employees love ChatGPT but can only use Copilot for work — and where AI agents may soon be booking flights and clearing transactions with questionable accountability.

When the US Senate voted 99-1 early Tuesday morning to strip a provision from a sweeping tax package that would have banned states from regulating artificial intelligence, it wasn’t just delivering a blow to tech industry lobbyists — it was highlighting a reality that corporate compliance officers have been living with for years: AI technology is advancing faster than we can craft policies to rein it in.

The overwhelming rejection of what would have been a limited five-year moratorium on state AI laws means the existing regulatory patchwork will continue to expand. For corporate compliance, infosec, risk and governance professionals, this reality is nothing new, and companies will continue writing rules and policies even as the technology they’re making the rules about evolves apace.

If they’re not flying blind, they’re coming close: 93% of organizations have implemented AI, but 59% have no policies governing its use, according to a recent Kroll report. This risk nightmare cloaked as an efficiency dream is playing out in conference rooms and cubicles across the corporate landscape.

“I am still surprised that organizations are approaching AI governance within their organizations so casually,” said Asha Palmer, who is senior vice president of compliance solutions at Skillsoft, an online training company, and a strong advocate for well-governed AI in the workplace. “I believe that we have to get more intentional about our frameworks and making sure that they’re operationalized, because the risk can be high. The potential for impact and reputational damage can be pretty severe.”

How do you govern technology that evolves faster than you can write rules for it? The answer, according to experts and practitioners who are figuring it out in real time, isn’t to wait for regulatory clarity that may never come. It’s to build governance frameworks designed for permanent uncertainty — and to do it now.

The new normal

The unsettled landscape around AI in the corporate world is not owing only to regulatory uncertainty in the US and abroad; indeed, the technology itself makes traditional regulatory approaches obsolete.

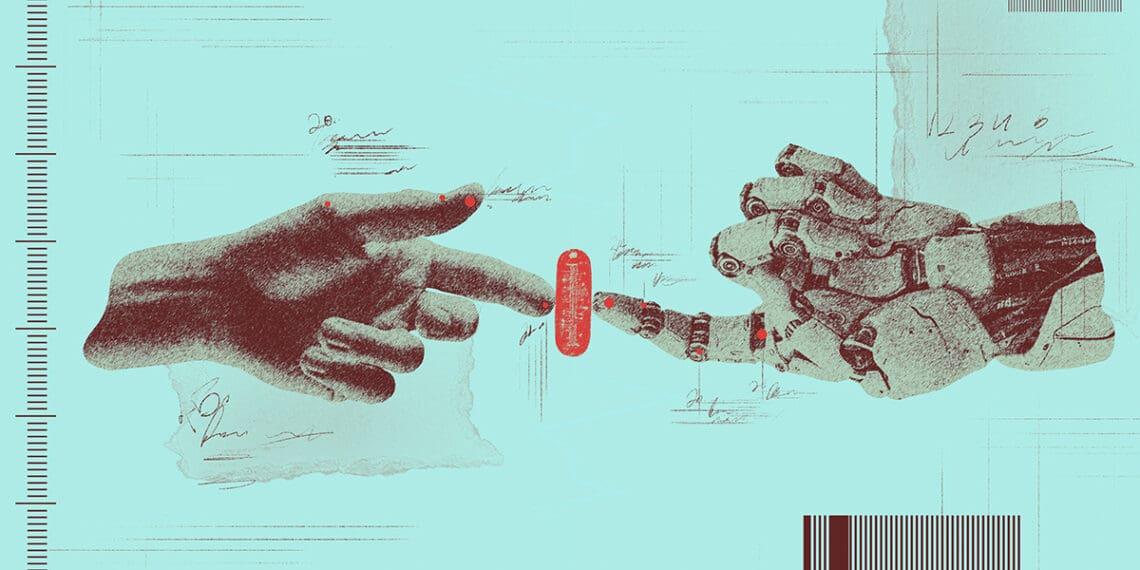

“We didn’t even know the words ‘agentic AI’ six months ago,” Palmer said. “Like, what is an agent? What can it do? Where does it go? How does it get this information? How does it go away and come back to me with something?”

With the EU AI Act already in effect and other international frameworks emerging, multinational companies face an increasingly complex regulatory landscape that no single piece of US legislation can untangle, though the proposed moratorium sought to calm things somewhat. Originally passing the US House of Representatives as a broad 10-year moratorium, a Senate deal changed it to a five-year pause with major limitations before it was overwhelmingly struck down.

This breakneck evolution means that by the time regulators craft rules for today’s AI capabilities, the technology has already moved on to something entirely different.

David Wheeler, leader of Neal, Gerber & Eisenberg’s cybersecurity and data privacy practice, puts the speed mismatch in stark terms: “A ten-year moratorium is going to be like a hundred years in real time. We’re going to be so far behind the eight ball, as this technology continues to develop and innovation continues to increase its ability to do certain things.'”

Managing the invisible

The challenge for corporate leaders isn’t just that regulations vary from state to state; it’s that AI itself is becoming increasingly invisible to the people trying to govern it, whether because employees are using their own preferred-but-unapproved tools or vendors are bundling the tech into their offerings in ways that aren’t always obvious.

And the scope of this shadow AI problem is becoming clearer as a new generation enters the workforce. According to a recent Resume Genius survey, 39% of Gen Z workers have used AI to automate tasks without their manager’s knowledge, and nearly one in five say they couldn’t do their current job without AI. These aren’t edge cases — they’re previews of a workforce that’s already AI-native and pushing boundaries in ways compliance teams may not be able to predict.

“We have approved for our organization Copilot; I love ChatGPT,” Palmer said, illustrating the personal preference problem that’s playing out in offices everywhere. “Well, if that’s my individual preference, what is my organization doing? Because ChatGPT is not an approved use case for organizational data.”

But even when workers stick to approved tools, generative AI has well-known limitations. For example, it has a tendency to deliver false information, something Palmer discovered firsthand when conducting personal research on property in Enfield, N.C., only to find the AI she was using had confidently provided information about Enfield, Conn., instead.

“Had I not clicked on that article and verified the information that it was giving me by following the citations, I would have given my mom and my grandmother all this false information,” she said.

This trust-but-verify burden becomes exponentially harder when AI is embedded in diverse processes and tools, making thousands of micro-decisions daily. And the problem is about to get more complex. Mike Cullen, a principal at Baker Tilly specializing in cybersecurity and IT risk, predicts that the next wave of agentic AI will create entirely new accountability challenges: “Even with some of the regulations that we have, it’s unclear what happens when the system is acting on behalf of someone else or some organization. Where does that actually end up falling if something goes wrong?” The question of whose agent booked that flight — or cleared that transaction — may be the next thing that keeps compliance officers up at night.

Embracing the unknown

Rather than waiting for regulatory certainty that will never arrive, compliance experts and legal observers recommend embracing governance frameworks — like NIST’s guidelines on AI risk — that are designed to bend without breaking.

“I think we do need some common-sense rules around certain things, especially when the AI technologies are used in a way that totally removes a human from a ‘high risk’ decision or process,” Cullen said. He recommends risk-based thinking: High-stakes decisions like healthcare treatments or insurance claims require human oversight, while lower-risk applications can operate with lighter governance. This mirrors the tiered risk structure of the EU AI Act, which categorizes AI systems from minimal to unacceptable risk levels.

Wheeler takes a similarly cautious but pragmatic approach. For his legal practice, he avoids AI entirely for case research and statute interpretation, high-stakes tasks where the risks of chatbot hallucinations are simply too high, but he sees value in experimentation for lower-risk applications.

Palmer advocates for what she calls “agile governance” — frameworks that can adapt as quickly as the technology evolves, which companies have done for previously disruptive technology like the internet or social media: “You govern what we have now, with the idea that you have to be adaptable as things develop,” she said. “It has to be with agility and on a continual basis.”

NIST’s AI risk management framework provides a starting point, but experts stress that companies need to customize it for their specific risks and use cases. Palmer suggests building internal governance that meets “even possibly the most stringent of the regulations even where they may not directly apply to your org,” preparing for whatever regulatory requirements might emerge in the US or abroad.

Palmer also recommends incorporating employees’ preferences, when appropriate, such as by giving them a chance to request approval for new AI tools.

“Be vigilant for use cases that are outside of approved use cases,” Palmer said. “And then create a channel or feedback loop for your employees to say, ‘This would create great efficiency for us. I’ve used it. Can you vet it?’”

The skills evolution

Of course, business units aren’t the only ones using AI — compliance teams themselves are also seeing fundamental changes in the skills needed to do their jobs effectively. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity in a field that has often been slow to embrace new tech, Palmer said.

“How do we advance our profession and our antiquated ways of doing things with this technology that is so amazing and can help us when we have staffs of two and three people to deliver greater effectiveness and efficiency?” she said.

The skills gap is real and immediate. Wheeler’s technical background, including a B.S. in information systems, gives him insights many professionals, even compliance officers, may lack, which could signal trouble. Assembling a team with the right skillset is critical, Wheeler said.

“You have to understand what’s under the hood; you have to understand how this works before you can really make a sound decision about how to apply it. Your average marketer, your average human resources person, they don’t have that visibility,” Wheeler said. “So they’re looking at something [and saying], ‘Hey, this is going to make my job easier,’ not really understanding what it’s doing.”

This knowledge deficit isn’t just about understanding AI capabilities — it’s about being able to credibly guide organizations through decisions about tools they may not fully comprehend themselves. Palmer advocates for compliance professionals to develop their own AI literacy first: “I always say to our customers, who are a lot of conservative compliance folks … ‘How do you use it in your own life,’ and start there.”

Jennifer L. Gaskin is editorial director of Corporate Compliance Insights. A newsroom-forged journalist, she began her career in community newspapers. Her first assignment was covering a county council meeting where the main agenda item was whether the clerk's office needed a new printer (it did). Starting with her early days at small local papers, Jennifer has worked as a reporter, photographer, copy editor, page designer, manager and more. She joined the staff of Corporate Compliance Insights in 2021.

Jennifer L. Gaskin is editorial director of Corporate Compliance Insights. A newsroom-forged journalist, she began her career in community newspapers. Her first assignment was covering a county council meeting where the main agenda item was whether the clerk's office needed a new printer (it did). Starting with her early days at small local papers, Jennifer has worked as a reporter, photographer, copy editor, page designer, manager and more. She joined the staff of Corporate Compliance Insights in 2021.