Successful congressional testimony is not about how smart or articulate corporate leaders are but about three pillars: preparation, messaging and discipline, say Dan Small and Christopher Armstrong of Holland & Knight. In the first of a three-part series, the authors explain why the mindset of “I’ll just go in and tell my story” is a one-way ticket to disaster.

This is the first of a three-part series on how corporate leaders can prepare for congressional testimony. Coming up: messaging and discipline.

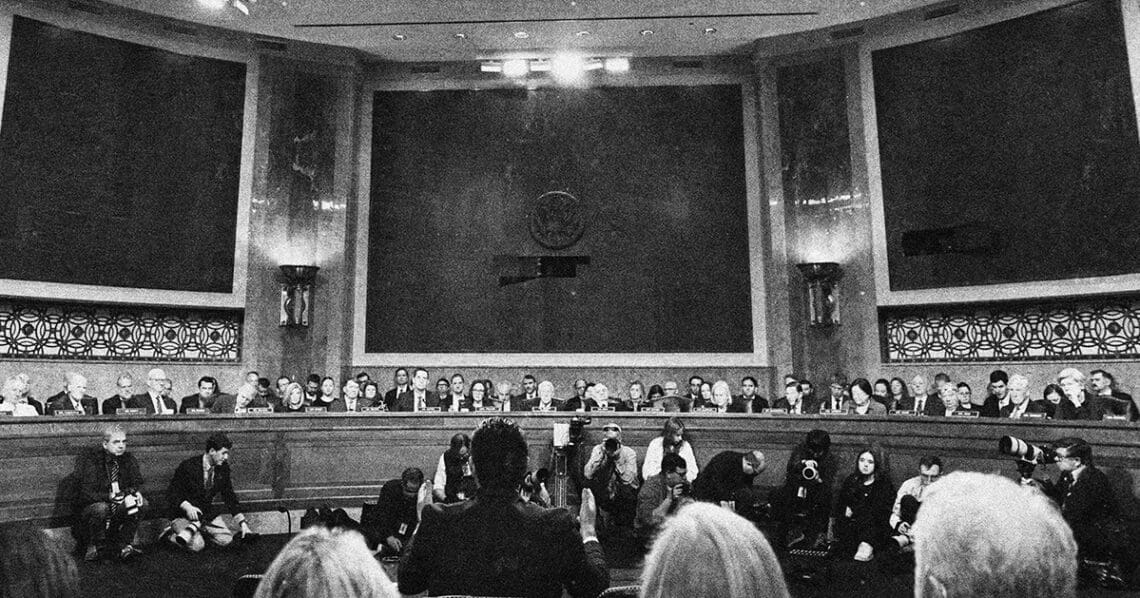

Entering the world of congressional testimony can often be a strange and high-risk experience (just ask Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos). Unlike traditional testimony in litigation, testimony before a congressional oversight committee can be part politics, part theatrics and part high-stakes communications. It is also potentially dangerous to your legal, reputational and policy interests.

Successful testimony is, simply put, not about how smart, articulate or successful you are. You may be all those things and more, but often, congressional hearings are about pushing a pre-established agenda, creating soundbites to support preconceived ideas and using witnesses as punching bags. The goal for the witness should not necessarily be to win a congressional hearing. It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to win as a witness, but it’s quite possible to lose. Instead, the goal is about minimizing risk, surviving and going about your life and business with your reputation intact afterward. Together, we have prepared CEOs, governors, federal government officials, university officials and well-known individuals for testimony. The only thing each has in common is the process we employed and the outcomes that inform what we call the three pillars of testimony.

Boiled down, these three pillars of successful congressional testimony are preparation, messaging and discipline. That’s what it’s about. These pillars have shown themselves in years of experience preparing clients to testify before Congress and in other settings, as well as being on the other side of the table planning strategy against witnesses.

Today, we deal with the first: preparation.

The General Counsel as Architect of the Board-CEO Relationship

When high trust exists, organizations surface issues earlier and manage crises with resilience

Read moreDetailsForewarned is forearmed

“Forewarned, forearmed, to be prepared is half the victory.” This quote is commonly attributed to “Don Quixote” author Miguel de Cervantes; it’s correctly applied here — and being forewarned, forearmed or prepared is not something that happens naturally. A congressional hearing is not a natural proceeding, which makes it difficult for intelligent, successful folks who are used to having a mindset that says, “I’ll just go in and tell my story!” Such a mindset is a recipe for disaster in this case.

What do we mean by preparation? When we get called in to prepare a witness for congressional proceedings, this is often the first — and toughest — battle. Preparation is not a quick and easy thing. Meeting for an hour or two, between all your other meetings, is not real preparation. Preparation is an intensive and extensive process that takes a number of steps. It requires an introduction, getting to know the lawyer, or whoever is preparing you, reviewing the facts, reviewing the process, putting it all together in a series of rules that we’ll talk about and working with counsel to anticipate problems and pitfalls. All typically under a tight timeline.

Despite what anyone says, congressional oversight hearings are rarely only about finding facts. To whatever extent anyone is interested, that work has usually been done behind the scenes by congressional staff, and hopefully by your staff as well.

From a preparation standpoint, that’s good news. It means that, together, we can usually figure out what the facts are, what the questions will be and therefore what the answers will be. With key questions, a hearing is not the time for spontaneity. Key or tough questions should be carefully considered, analyzed, answered and then practiced over and over, well before the actual hearing. Far too often, witnesses are asked questions that could — and should — have been fully anticipated and prepared for, only to fumble with a spontaneous answer, sometimes disastrously. Language matters; context matters; tone matters: All this and more should have been developed and practiced in advance.

There’s a great quote from a famous trial lawyer, which although intended for closing argument at trial, applies equally well here: “It’s simply not possible to powerfully articulate a great number of points, one immediately following another, extemporaneously. There is a best way to make a point, and to find it takes time and sweat on the yellow pad.”

The next critical step in real preparation is a dry run. We can learn from Dan’s traumatic experience teaching his twin girls how to ride bicycles years ago. Try as he might, he could not teach them how to ride bicycles just by talking to them. Sooner or later, they had to get on the darn things, with all of the bumps and bruises, the tears, and yes, the joy that came with it.

We feel the same way about working with witnesses. We can accomplish a great deal by talking with each other, but sooner or later, you have to get on the bicycle. Sooner or later, you have to do a dry run. We don’t mean the occasional, “well, if they ask you this, what do you think?” We mean stopping the preparation process and saying, OK, for the next two hours, four hours, whatever it takes, we’re going to do a dry run. In-role, hardball, uninterrupted. Then we’ll break down answers, tone, demeanor, discuss and do it again. And maybe again.

The more realistic it is, the more helpful it will be. The questioners should not only be your internal team or people you are already comfortable with. If you want to be nice and play patty-cake, do it somewhere else. We’re not preparing you for patty-cake. This is a serious undertaking. You have to treat it seriously. Do a dry run, then stop, talk about it and do it again.

The goal of every dry run, remarkable as this may sound, is that the witness comes out of the actual interview or testimony, or whatever the process is, and turns to us, as many of our witnesses do, and says, “Oh, you guys were tougher than that!” That’s the goal of a dry run.

The next steps are reviewing the process (discipline) and reviewing the core themes (message). Those are the basic steps to this extensive and intensive process. In our next two articles, we’ll address these other pillars.

Dan Small

Dan Small Christopher Armstrong

Christopher Armstrong