This article was republished with permission from Tom Fox’s FCPA Compliance and Ethics Blog.

While the indictments last week against 14 individuals who were members of or associated with Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) did not include any alleged violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), it does not necessarily mean that companies subject to the Act are in the clear. There can be another avenue for FCPA liability: under the Travel Act. In the 2013 and 2014 FCPA enforcement actions involving Direct Access Partners (DAP) defendants, Tomas Clarke, Alejandro Hurtado and Maria Gonzalez were also charged with conspiracy to violate the Travel Act. Hurtado and Gonzalez were charged with substantive Travel Act violations.

As stated in the FCPA Guidance, “The Travel Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1952, prohibits travel in interstate or foreign commerce or using the mail or any facility in interstate or foreign commerce, with the intent to distribute the proceeds of any unlawful activity or to promote, manage, establish or carry on any unlawful activity. “Unlawful activity” includes violations of not only the FCPA, but also state commercial bribery laws. Thus, bribery between private commercial enterprises may, in some circumstances, be covered by the Travel Act. Said differently, if a company pays kickbacks to an employee of a private company who is not a foreign official, such private-to-private bribery could possibly be charged under the Travel Act.”

The Travel Act elements are:

(1) use of a facility of foreign or interstate commerce (such as email, telephone, courier, personal travel);

(2) with intent to promote, manage, establish, carry on or distribute the proceeds of;

(3) an activity that is a violation of state or federal bribery, extortion or arson laws or a violation of the federal gambling, narcotics, money-laundering or RICO statutes.

This means that if, in promoting or negotiating a private business deal in a foreign country, a sales agent in the U.S. or abroad offers and pays some substantial amount to his private foreign counterpart to influence his acceptance of the transaction, and such activity may be a violation of the state law where the agent is doing business, the Justice Department may conclude that a violation of the Travel Act has occurred. For instance, in the state of Texas, there is no minimum limit under its Commercial Bribery statute (Section 32.43, TX. Penal Code), which bans simply the agreement to confer a benefit which would influence the conduct of the individual in question to make a decision in favor of the party conferring the benefit. As noted further in this article, the state of California bans payment of more than $1,000 between private parties for the purposes of influencing a business decision.

The DAP enforcement action was not the first case to use the Travel Act in conjunction with the FCPA. As was reported in the FCPA Blog, there was the matter of U.S. v. David H. Mead and Frerik Pluimers, (Cr. 98-240-01) D.N.J., Trenton Div. 1998. In this case, defendant Mead was convicted following a jury trial of conspiracy to violate the FCPA and the Travel Act (incorporating New Jersey’s commercial bribery statute) and two counts each of substantive violations of the FCPA and the Travel Act. In its 2008 article entitled “The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act: Walking the Fine Line of Compliance in China,” the law firm of Jones Day reported the case of United States v. Young & Rubicam, Inc., 741 F.Supp. 334 (D.Conn. 1990), where a company and individual defendants pleaded guilty to FCPA and Travel Act violations and paid a $500,000 fine.

In addition to the Mead and Young and Rubicam cases, the FCPA Guidance specifies that the Department of Justice (DOJ) has “previously charged both individual and corporate defendants in FCPA cases with violations of the Travel Act. For instance, an individual investor was convicted of conspiracy to violate the FCPA and the Travel Act in 2009 where the relevant “unlawful activity” under the Travel Act was an FCPA violation involving a bribery scheme in Azerbaijan. Also in 2009, a California company that engaged in both bribery of foreign officials in violation of the FCPA and commercial bribery in violation of California state law pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA and the Travel Act, among other charges.”

What does this mean for U.S. companies doing business overseas? The incorporation of the Travel Act into an FCPA prosecution could blur the distinction between bribery of foreign governmental officials and private citizens, if all foreign private citizens can be brought in under the FCPA by application of the Travel Act. U.S. companies doing business overseas that have a distinction in their FCPA compliance policies between gifts for and travel and entertainment of employees of private companies and employees of state-owned entities or foreign officials should immediately rethink this distinction in their approach.

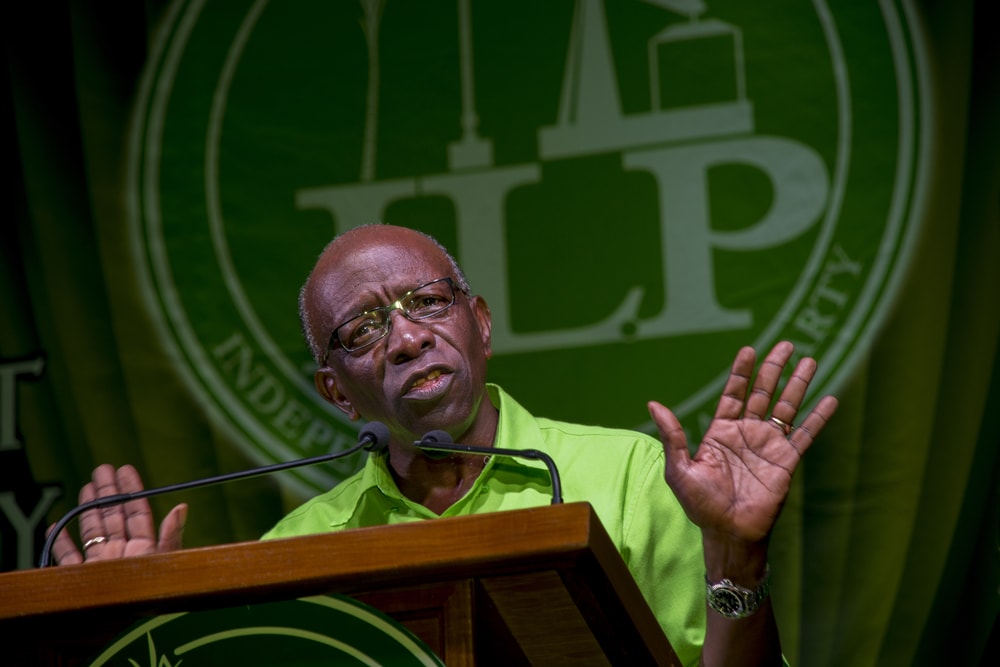

Further, and more importantly for the burgeoning FIFA scandal, the Travel Act may provide the basis for the DOJ to evaluate the conduct of the U.S. companies who are involved with marketing efforts directly with FIFA, regional soccer federations such as Concacaf and its former official Jack Warner from Trinidad or national soccer federations such the Brazilian national soccer federation, which was the beneficiary.

Indeed, as reported in the Wall Street Journal by Sara Germano, in an article entitled “Nike Says FIFA Indictment Doesn’t Allege Criminal Conduct By Company,” the FIFA “indictment didn’t mention Nike but alleged that a representative for a company described as ‘Sportswear Company A’ agreed to be invoiced by the firm and made $30 million in payments to a middleman between 1996 and 1999. Parts of those payments were then used as bribes and kickbacks, according to the indictment. Nike signed a sportswear outfitting deal with the Brazilian federation in 1996, according to the company website. Nike said Wednesday it has cooperated with the authorities and continues to do so.” In the article, Nike also denied any involvement in the bribery schemes. Germano wrote, “‘The charging documents unsealed yesterday in Brooklyn do not allege that Nike engaged in criminal conduct,’ the company said in an emailed statement. ‘There is no allegation in the charging documents that any Nike employee was aware of or knowingly participated in any bribery or kickback scheme.'”

In an article in the New York Times entitled “How a Speck in the Sea Became a FIFA Power,” Jeré Longman wrote about the alleged charitable donations made to the Cayman Islands Football Association (CIFA) to construct soccer facilities in the island nation. Yet many have never been constructed and the money is not accounted for. If the actions engaged in by any U.S. company involved in marketing efforts with FIFA, regional soccer federations or national soccer federations violated the state laws regarding commercial bribery where the U.S. companies were headquartered, there could be an argument that a FCPA violation could be incorporated through the Travel Act.

This publication contains general information only and is based on the experiences and research of the author. The author is not, by means of this publication, rendering business advice, legal advice or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such legal advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified legal advisor. The author, his affiliates and related entities shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person or entity that relies on this publication. The author gives his permission to link, post, distribute or reference this article for any lawful purpose, provided attribution is made to the author. The author can be reached at tfox@tfoxlaw.com.

Thomas Fox has practiced law in Houston for 25 years. He is now assisting companies with FCPA compliance, risk management and international transactions.

He was most recently the General Counsel at Drilling Controls, Inc., a worldwide oilfield manufacturing and service company. He was previously Division Counsel with Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. where he supported Halliburton’s software division and its downhole division, which included the logging, directional drilling and drill bit business units.

Tom attended undergraduate school at the University of Texas, graduate school at Michigan State University and law school at the University of Michigan.

Tom writes and speaks nationally and internationally on a wide variety of topics, ranging from FCPA compliance, indemnities and other forms of risk management for a worldwide energy practice, tax issues faced by multi-national US companies, insurance coverage issues and protection of trade secrets.

Thomas Fox can be contacted via email at tfox@tfoxlaw.com or through his website

Thomas Fox has practiced law in Houston for 25 years. He is now assisting companies with FCPA compliance, risk management and international transactions.

He was most recently the General Counsel at Drilling Controls, Inc., a worldwide oilfield manufacturing and service company. He was previously Division Counsel with Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. where he supported Halliburton’s software division and its downhole division, which included the logging, directional drilling and drill bit business units.

Tom attended undergraduate school at the University of Texas, graduate school at Michigan State University and law school at the University of Michigan.

Tom writes and speaks nationally and internationally on a wide variety of topics, ranging from FCPA compliance, indemnities and other forms of risk management for a worldwide energy practice, tax issues faced by multi-national US companies, insurance coverage issues and protection of trade secrets.

Thomas Fox can be contacted via email at tfox@tfoxlaw.com or through his website